Exhibition 07

Tables! Tables! Tables!

Photograph: Pippa Drummond. Styling: Natasha Felker.

Changes in the way we live impact the design of our environment. The reverse is also true. The design of the built environment, including furniture, impacts the way we live. At Industrial Facility, the design practice I cofounded with my partner Sam Hecht, we recognize this dynamic as we strive for what we call equilibrium—a balancing act that imbues our work with “just enough” design. We believe this kind of self-imposed restraint leads to products that are more sensible, purposeful, unexpected, contextual, and lasting.

Like the Eameses, we are a multidisciplinary practice. Sam is very much an industrial designer. Like Charles, my training is in architecture. Although neither of us are abstract artists, we share the same kind of productive push and pull that allows us to address solutions (and problems) from a variety of perspectives and at a range of scales—not just through the lens of one discipline’s concerns. Generally, Sam is consumed with questions of materiality and method of manufacture, and I am more likely to be engaged with a design’s relationship to culture, behavior, and place—the meaning it either suggests or acquires in our lives. In our practice, equilibrium arises from satisfying more than one system of thought.

As designers, we see opportunities to improve upon the past by navigating cultural shifts, technological change, material advancement, and environmental concerns. Sometimes we develop entirely new solutions or typologies, but, for us, it can also be achieved in principle for everyday things like chairs and tables. In the collection of Eames tables gathered here, I see a similar spirit of inquiry—of both understanding and propelling broader changes in the world in which they lived and worked.

Industrial Facility’s Kim Colin in her London studio surrounded with tables designed for Fucina, Herman Miller, Mattiazzi, and Takt Copenhagen. Photograph: Ben Anders

Today the word “industrial” has seemingly lost its ability to signify the promise of something better (as we grapple with consequences), whereas when we look to the example of the Eameses, their ability to harness it as a hopeful strategy signals a significant aspect of their legacy. Ray and Charles embraced industrialism and saw mass production as a way of making higher quality things available to more people, inexpensively (summarized succinctly in the oft repeated Eamesian mantra: “the best, for the most, for the least”). In previous generations furniture designers were hands-on practitioners with carpentry or woodworking skills and were limited to what they could create in their own shop, whereas the Eameses became masters of industrial craft at a global scale—a pioneering model we continue, with requisite care, to explore and refine today. They were not constricted by the style or taste of the time, but rather, they shaped it by adopting new materials and technologies and making them desirable and human scale. They never lost sight of the fact that a mass-produced product still must appeal to the individual, and its eventual success depends on the ability for those individuals to make it their own. This openness is part of the enduring appeal.

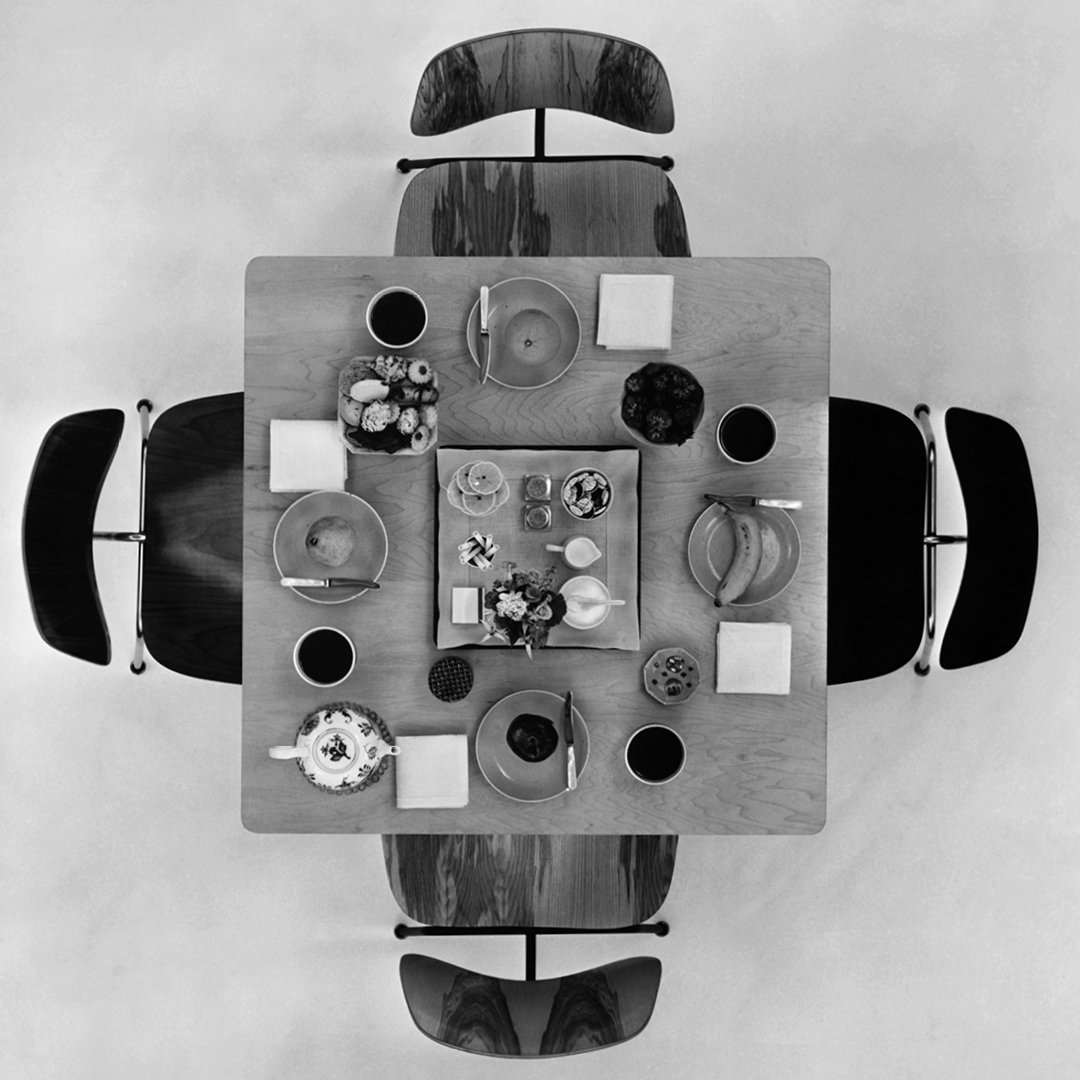

An early promotional photograph by Ray and Charles Eames shows molded plywood chairs surrounding a CTM. © Eames Office, LLC

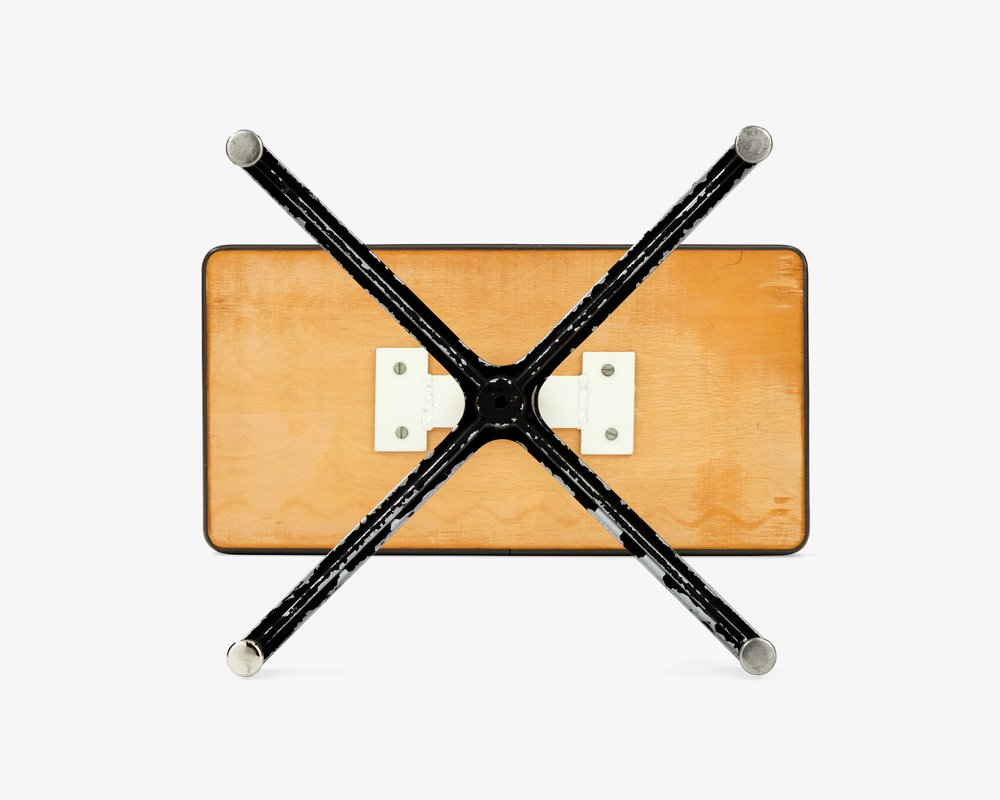

This early CTM (Coffee Table Metal) from our collection features legs in “bright metal” and a somewhat ad hoc method of attaching the top.

While chairs so often take center stage in conversations around design, and certainly Eames design, tables are particularly interesting because of how simple they are conceptually, and yet, how critical they are in our lives and environments. Relieved from the complexity of supporting the seated body, a table’s basic function is to hold up what is placed upon it. But they are also territorial—useful obstacles that can define a room’s purpose and our path through it. Variations in materiality, shape, and height, can prompt wildly different interpretations for use, with equally wide discrepancies across cultures. The same primary elements combine to convey character—how a design speaks to us, relates to other furnishings, and shapes the setting in which it is placed.

The Eames tables presented here—from one-off prototypes that test a technique or idea, to iterations that show how designs continued to be developed, to production models that offer a window into their systemic design approach, to more personal customizations—demonstrate the designers’ thoughtful approach. While the chairs may have gotten the bulk of the attention, the Eameses showed that tables are equally important and useful cohabitants. They literally set the table for how we live with them now.

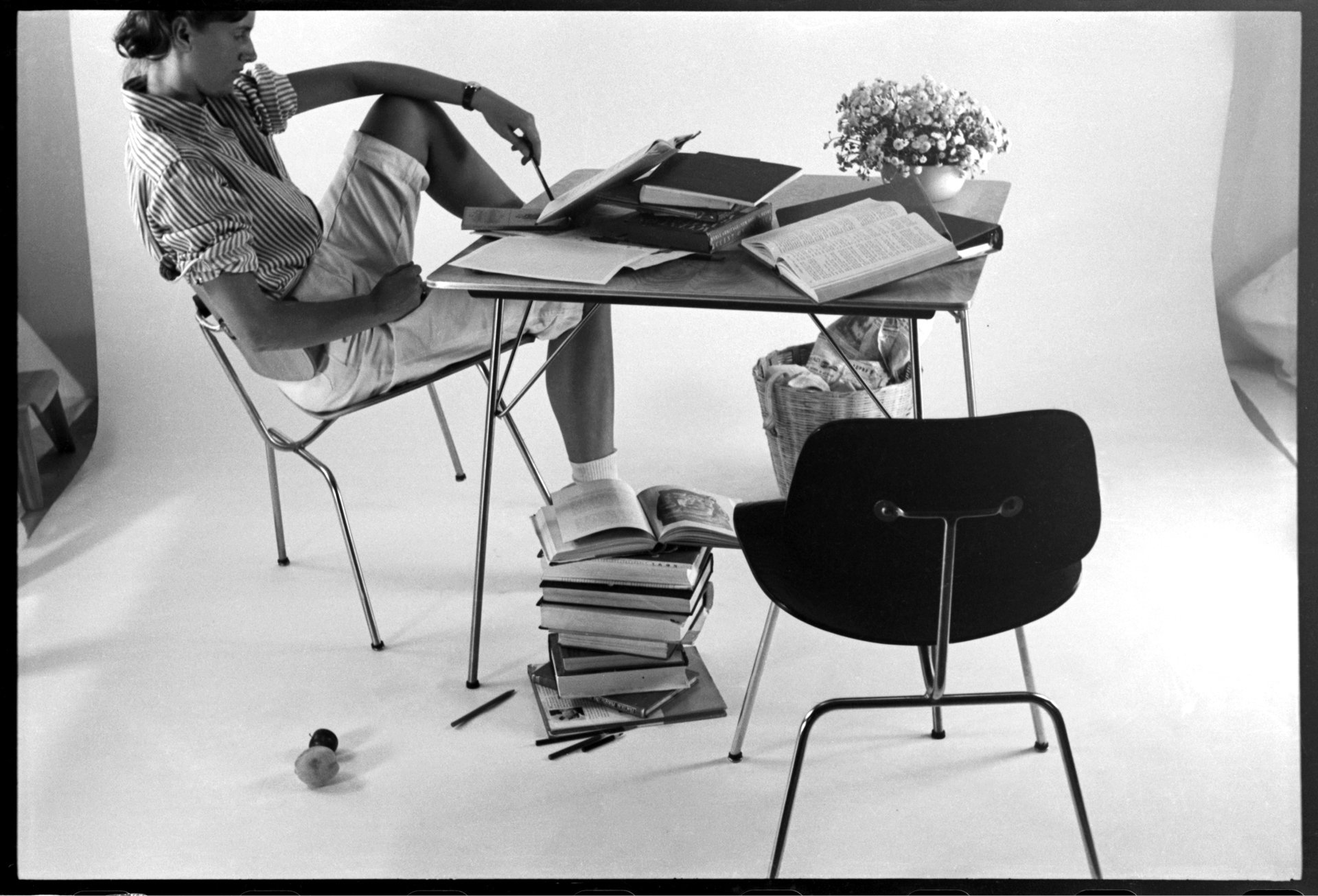

A young Lucia Eames models one potential use for the folding DTM (Dining Table Metal). © Eames Office, LLC

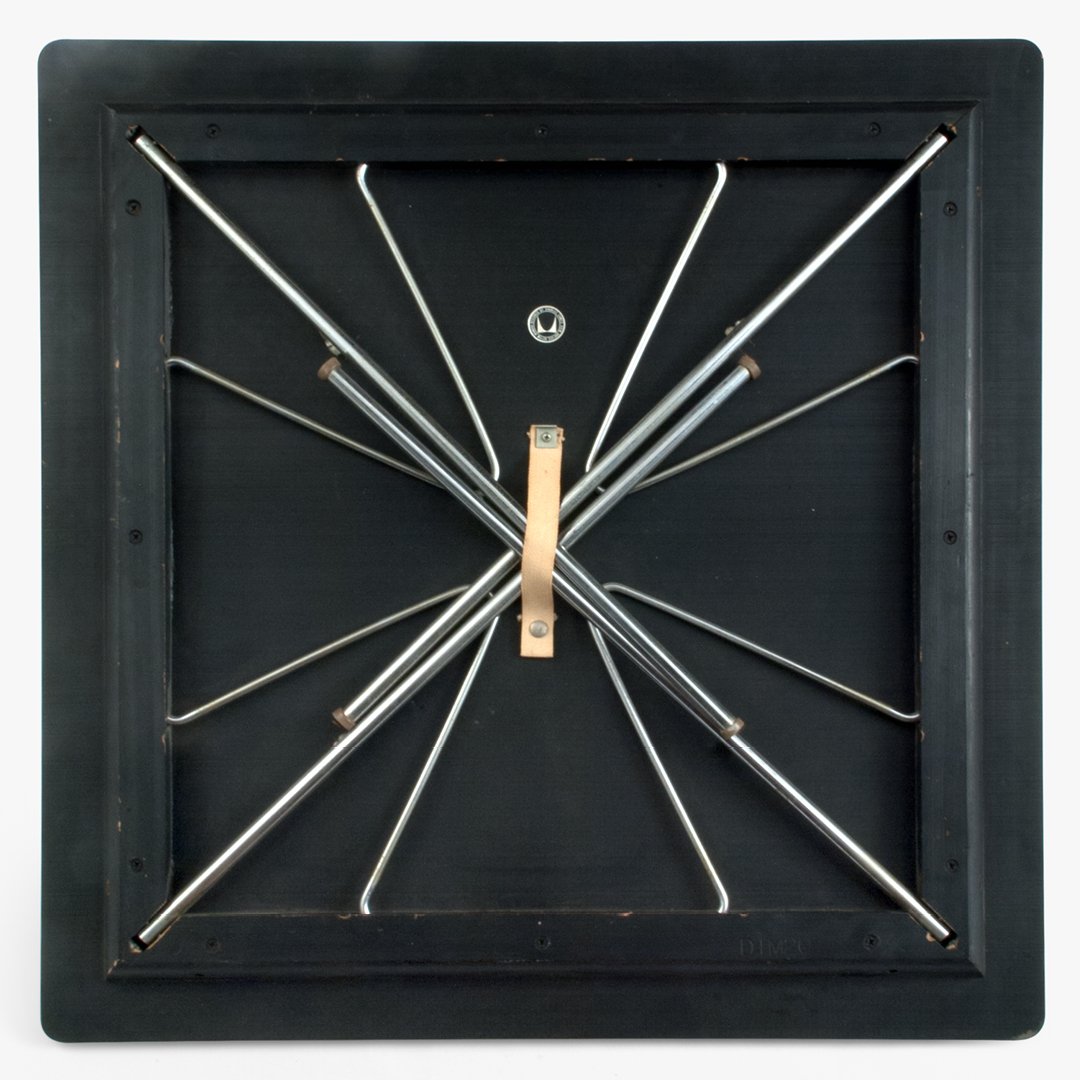

These are tables with an ideal: they should be beautifully purposeful when full or empty, with people around them or left alone in a room; they should be as thoughtfully considered from above as below, with quality connections and materials that give life to the product from every angle; they should offer goodness not only in use, but also during production, shipping, and storage; they should support wide ranging activity, only limited by imagination over time.

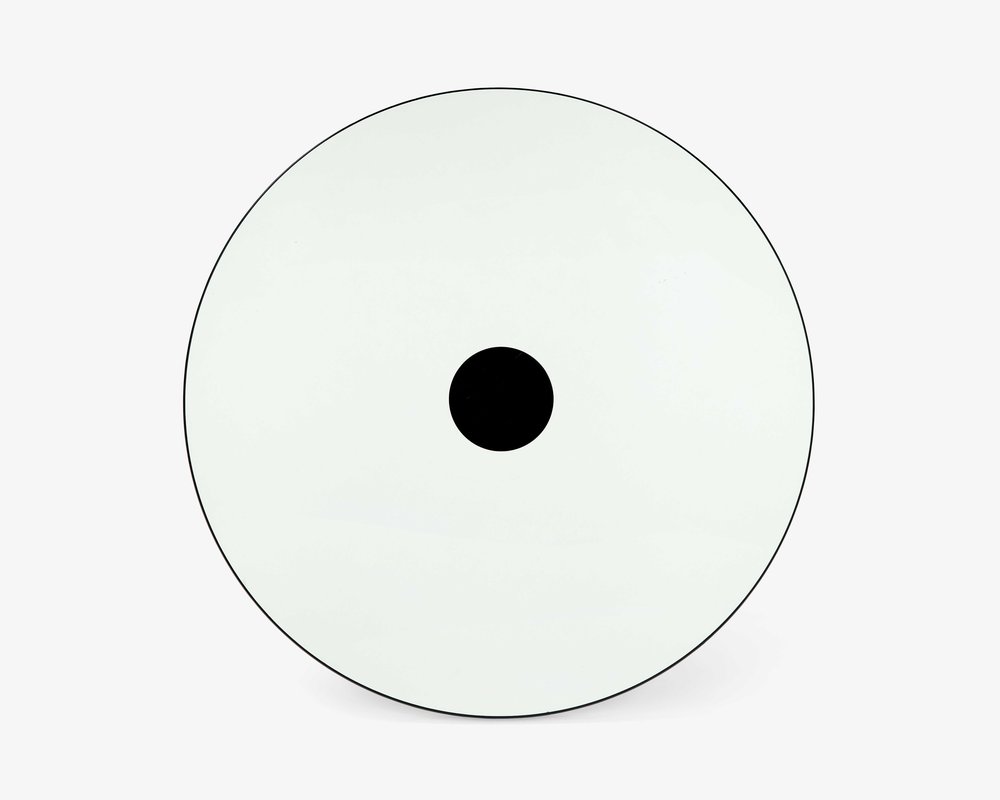

These sentiments were echoed in the advertisements, brochures, and catalogs the Eameses developed to promote their work. They proposed cinematic ways of showing their designs, framing photos as partial landscapes that were suggestive of a situation or usage that was not closely defined or prescribed. They suggested rooms, but not their designation or location. They framed views—like from directly overhead, or at ground level looking up—that we would never quite see in real life, both to impose a level of abstraction that allows us to see things differently, as well as to celebrate the possibilities and potential inherent in the product. They nudged the viewer, suggesting that tables could be part of the fabric of any place—even the outdoors!—no longer just an object in a room. We cannot underestimate how radical this was at the time and also note how the Eameses’ influence has helped it to become somewhat conventional by today’s standards.

An overhead view of a DTM suggests use while also reducing the table and its content to a level of graphic abstraction. © Eames Office, LLC

The underside of the DTM, with its neatly folding legs and canvas buckle, is as thoughtfully considered as its top.

In the intervening decades between the Eameses’ design practice and the formation of our own, the world has changed in innumerable ways. Today, rooms at home and in offices no longer have the luxury of a single purpose; they are increasingly multipurpose or mixed-use places, able to accommodate change and transform to new needs rather quickly. Mobile, digital connectivity has enabled us to work or create anywhere, and freed us from the spatial demands and specificity of technological installations—much of which fell on tables. Instead, tables are now less often the centerpieces of rooms and have become more like supporting pieces in a varied landscape where anything goes (functionally, behaviorally, and positionally) and everything that can change will, eventually.

In our own work for companies like Emeco, Herman Miller, Mattiazzi, and TAKT, we delve deeply into these cultural shifts to inform the reasoning behind a new design, and the ultimate expression that design takes as it becomes a manufactured product. The tables we have designed for these companies are not biographical or purpose-built for one task, or suited to one space, but each, in its own way, offers a unique set of qualities that allow them to hold long-lasting relevance. It’s because tables are inherently multidimensional—not only in their metrics but more importantly in how they allow for life to be played out. If the Eameses taught us anything, it is that the more multidimensional a design is, the greater chance it has to be absorbed into everyday life. ❤

—Essay by Kim Colin

Photograph: Pippa Drummond; Styling: Natasha Felker

Explore All Artifacts

Dive into the exhibition—item by item. Clicking on an entry takes you to an artifact detail page containing pertinent details, more images, and in the case of some objects, curatorial notes.