Exhibition 06

Ray’s Hand

Ray Kaiser Eames (1912–88) trained as an artist and Charles as an architect but they each brought many more skills and interests to what—beginning with their marriage in 1941—became one of the most creative partnerships of the twentieth century; one that mainly covered design (from furniture and toys to exhibitions), short films (over 125), and multimedia presentations, rather than architecture or fine art.

Among the many other things the Eameses shared was a holistic approach to, and contagious enthusiasm for, life, work, and play, happily blurring boundaries while embracing their “inner child” and melding seriousness with fun. Charles died in 1978; Ray a decade later to the very day, as if to maintain their symbiotic connection even in death.

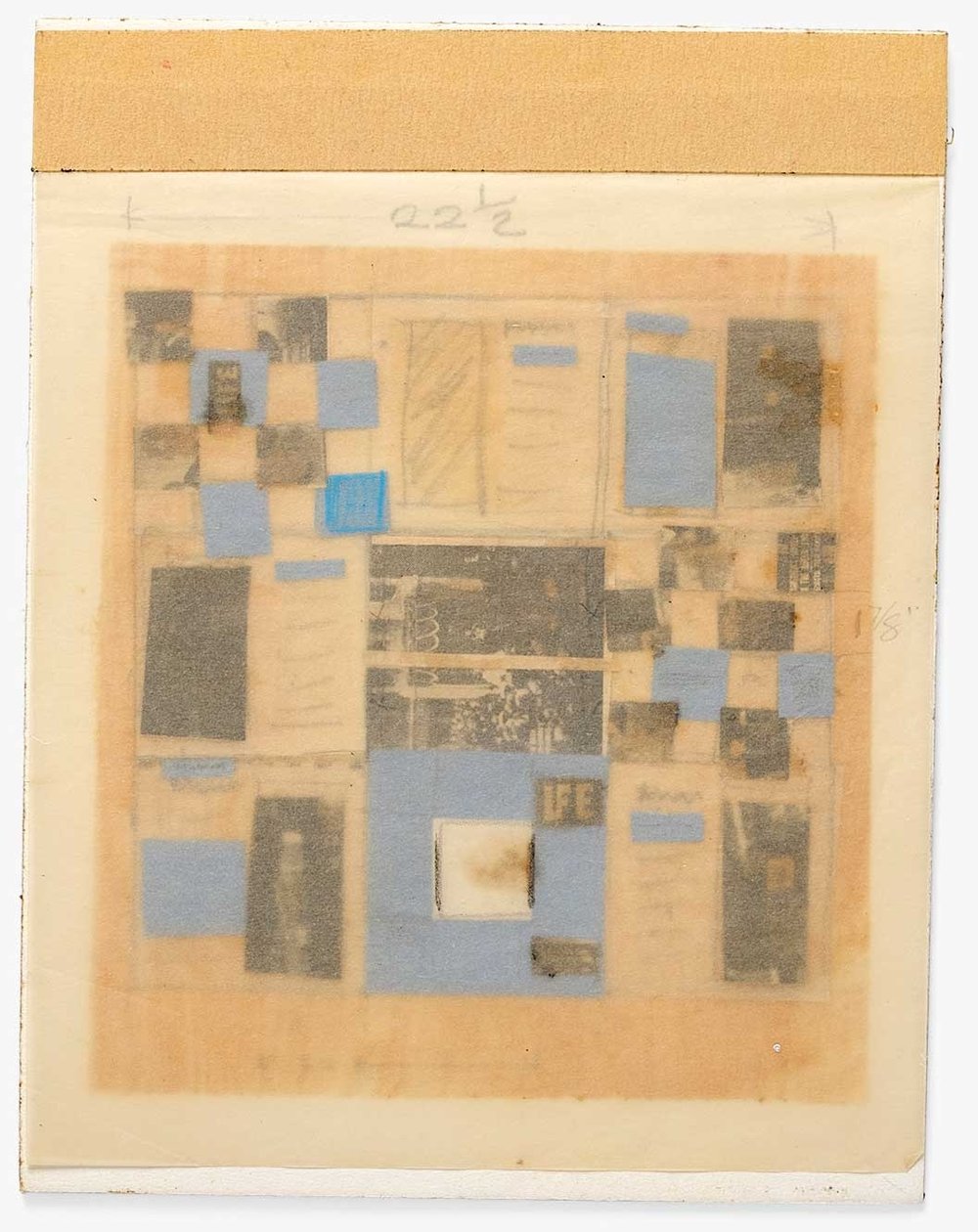

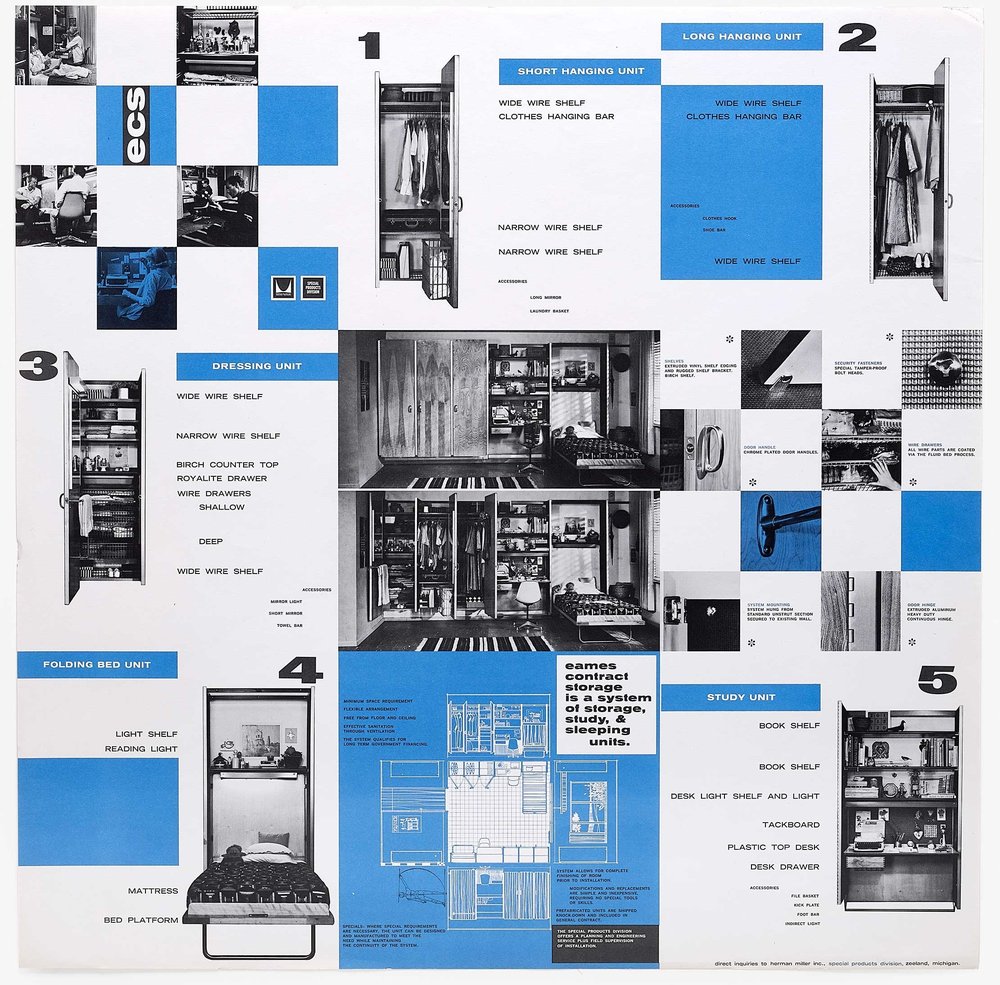

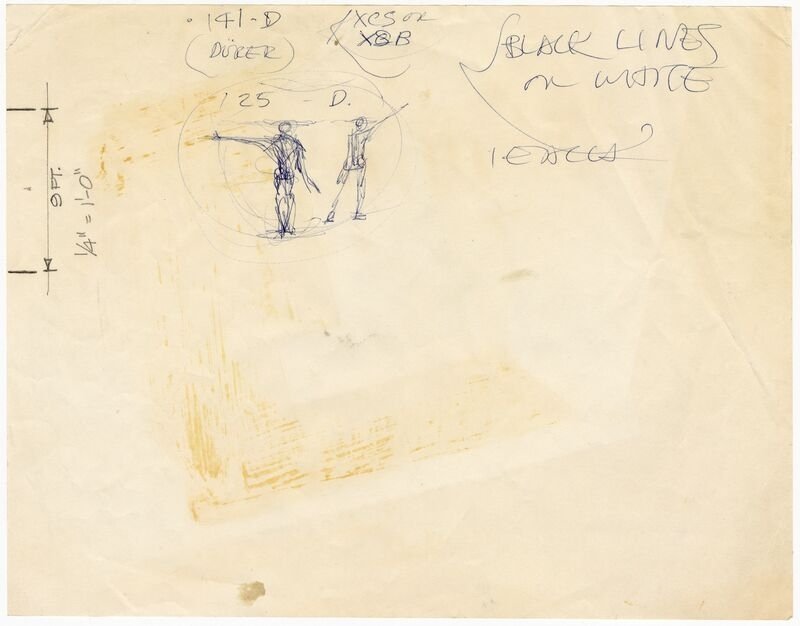

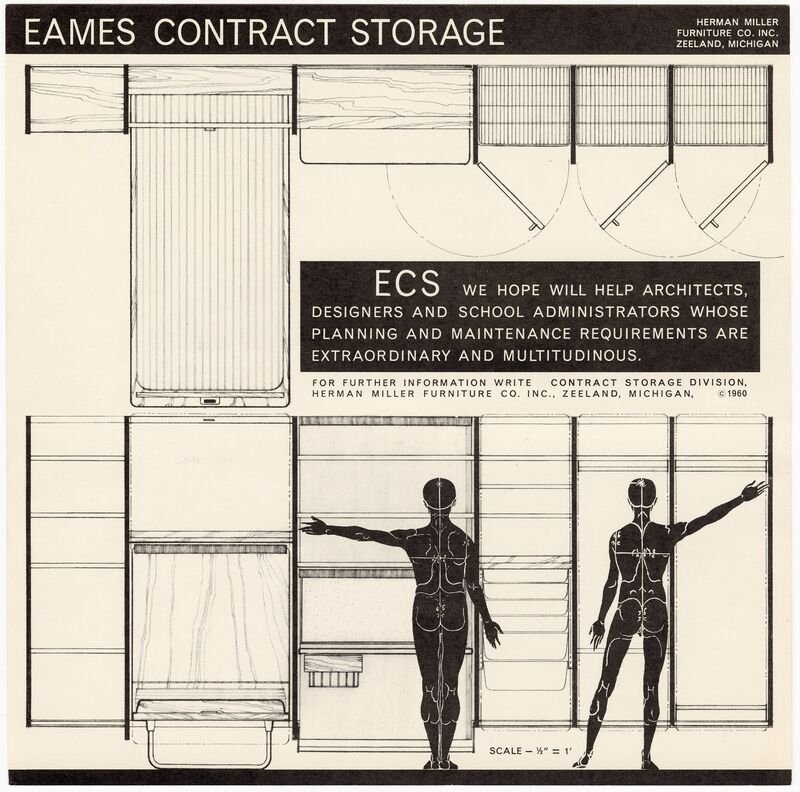

Ray, in May 1960, working on a color and compositional study of the projections exhibition for Mathematica: A World of Numbers… and Beyond. Image © Eames Office, LLC

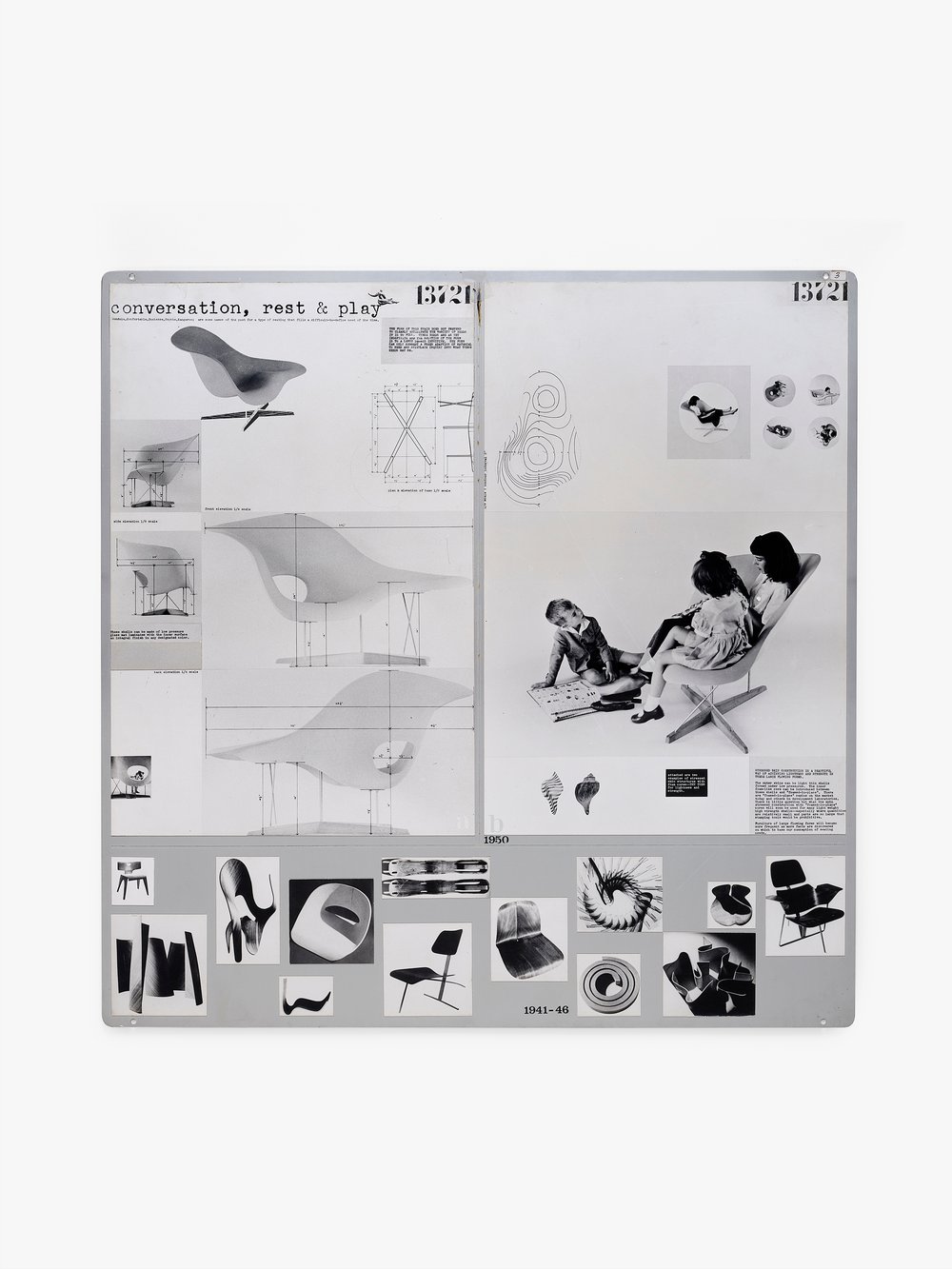

The spotlight here is on Ray who, especially early in their partnership, was often presented as Charles’s “artist wife” and/or as “helping” him in his work. Even though she was sometimes acknowledged as a full partner thereafter, her centrality to the partnership tended to get lost for various reasons, from her modesty and Charles’s greater public profile when they met to wider societal issues, including systemic sexism. Charles appreciated Ray’s multifarious talents better than anyone, and when, in 1965, Current Biography included an entry for him alone, it quoted him as stating that Ray was “equally responsible” with him “for everything that goes on here [the Eames Office].” When emphasizing her importance, he often cited her interest in structure honed during six years studying with European émigré artist Hans Hofmann, or claimed “Anything I can do, Ray can do better.” He also commented on her ability to hold complete projects in her head, including complex exhibitions, at the same time as attending to the minutest of details, which is akin to Ray expressing one of her roles as keeping “the big idea” in mind while looking critically at the work.

Ray’s training in abstract painting was evident in her approach to color and form—as with this design for Mathematica: A World of Numbers… and Beyond. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Found within the drawer labeled “Scraps” from the Eames Office graphics room are two cigarette packages labeled “Little Scraps.”

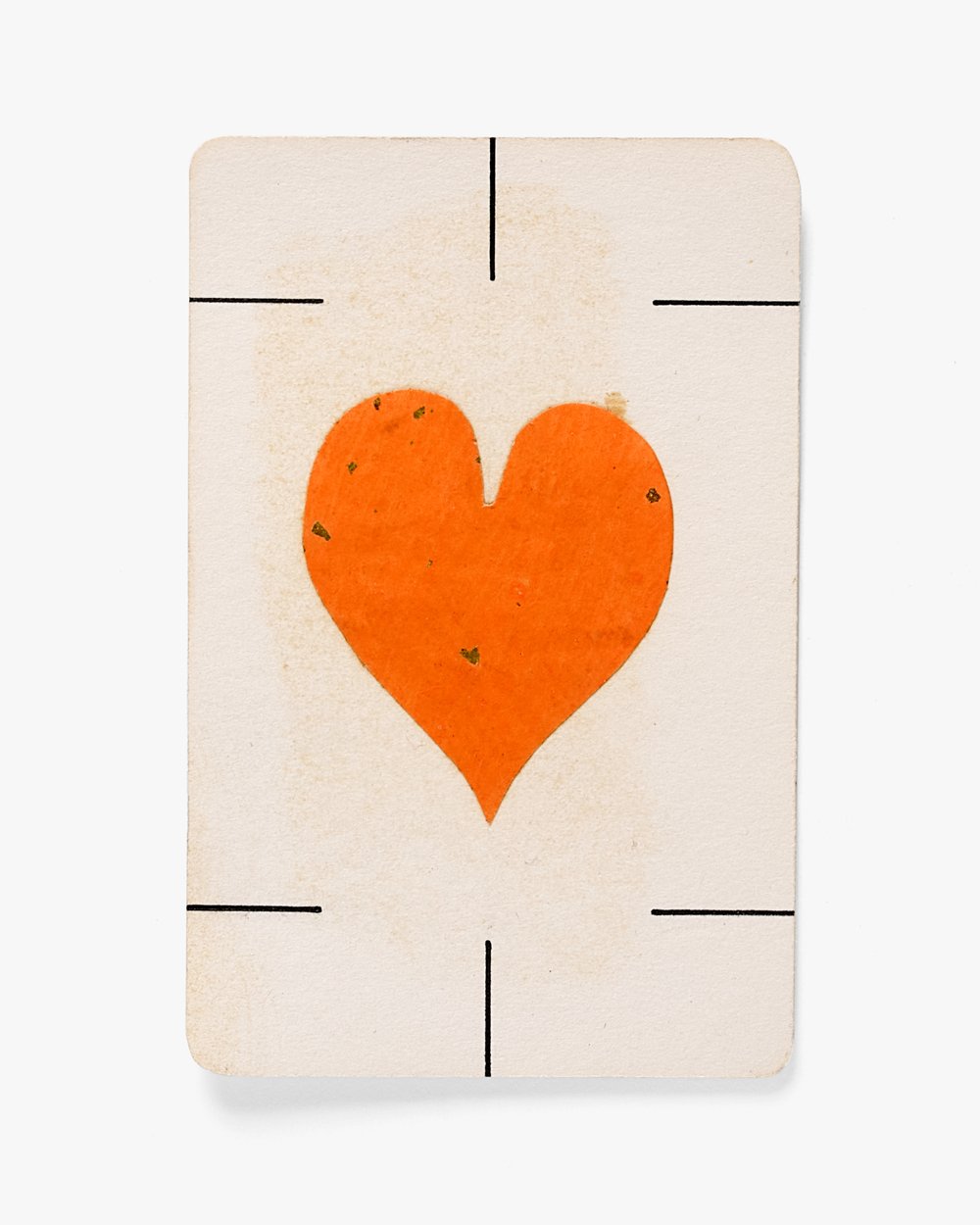

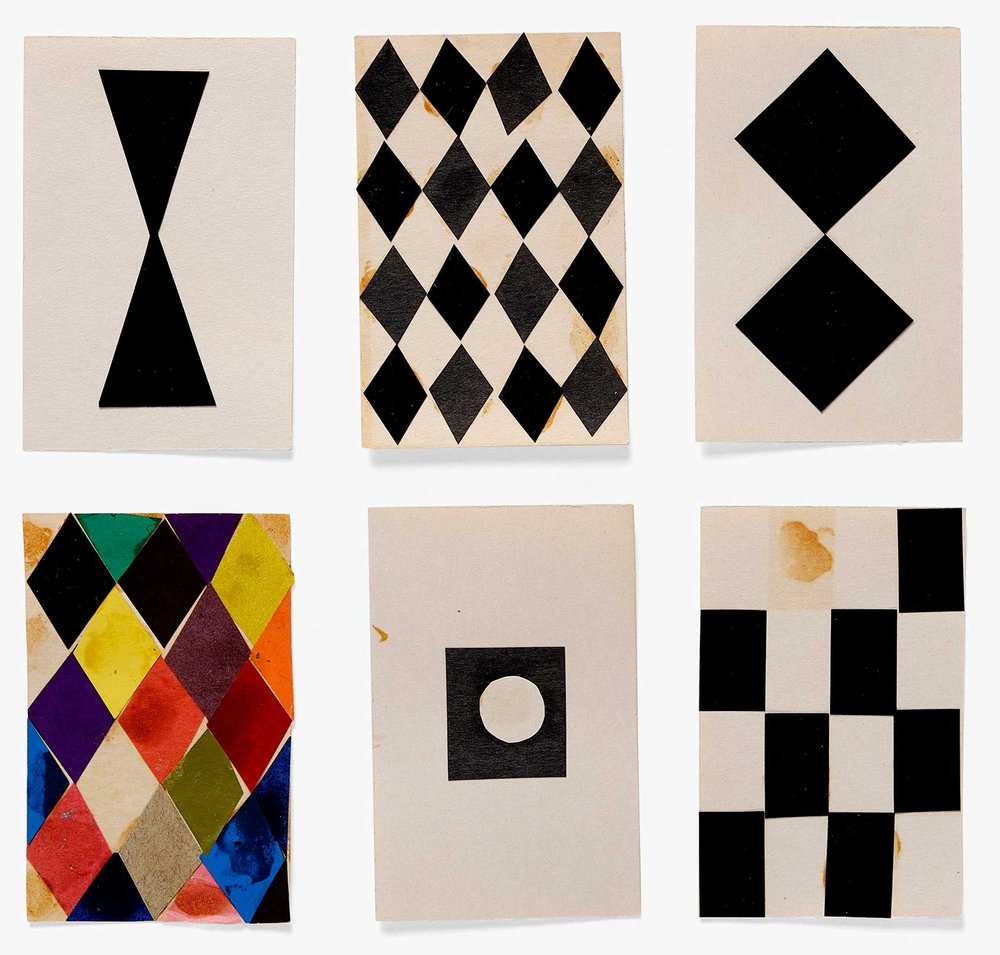

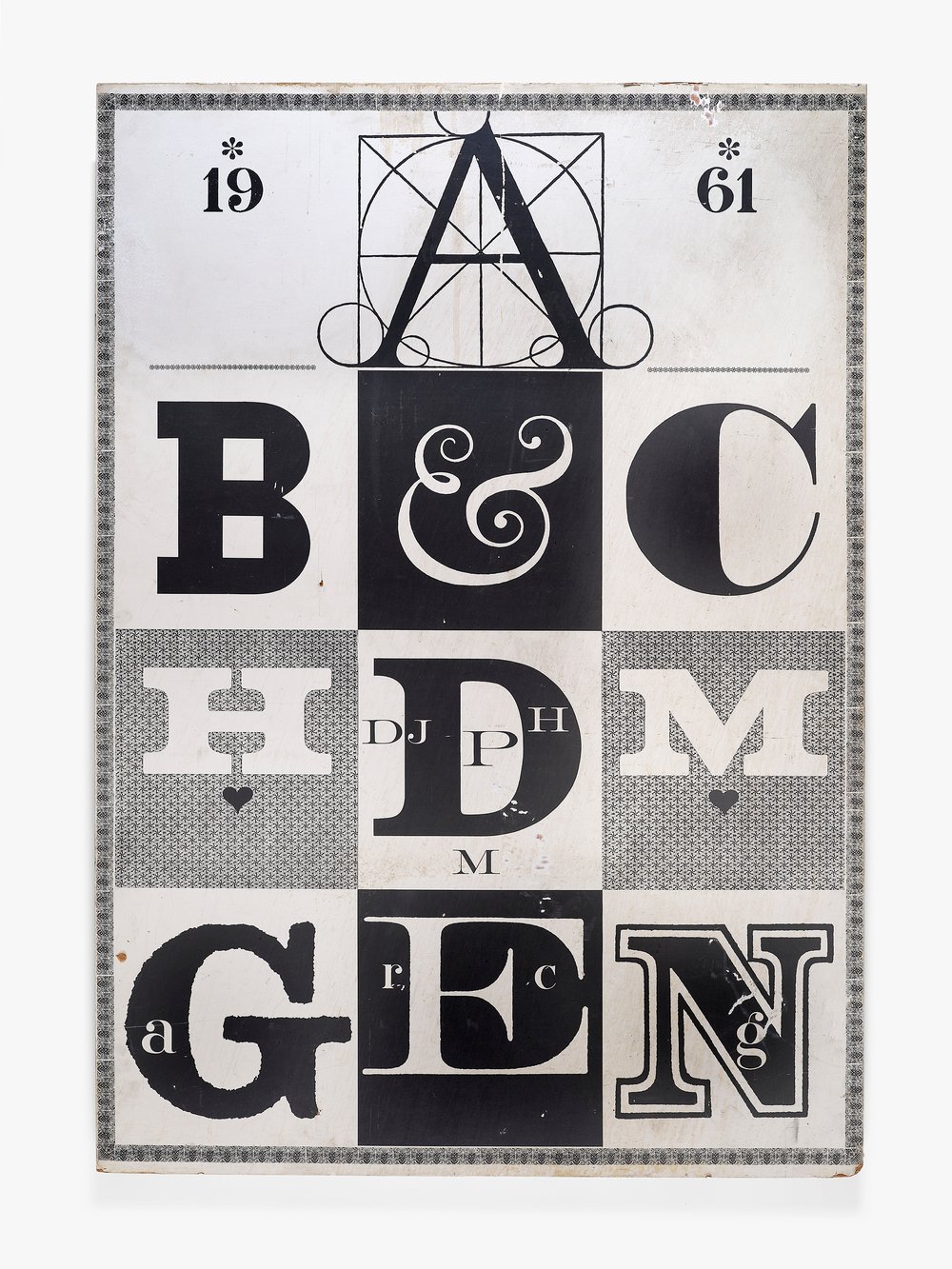

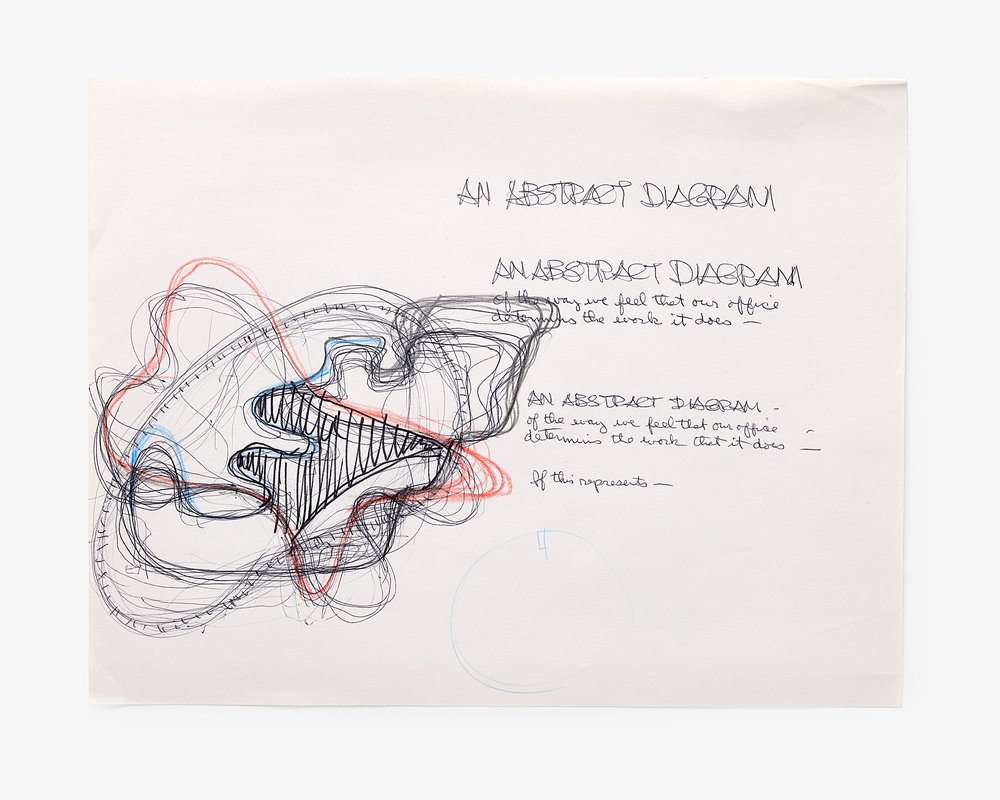

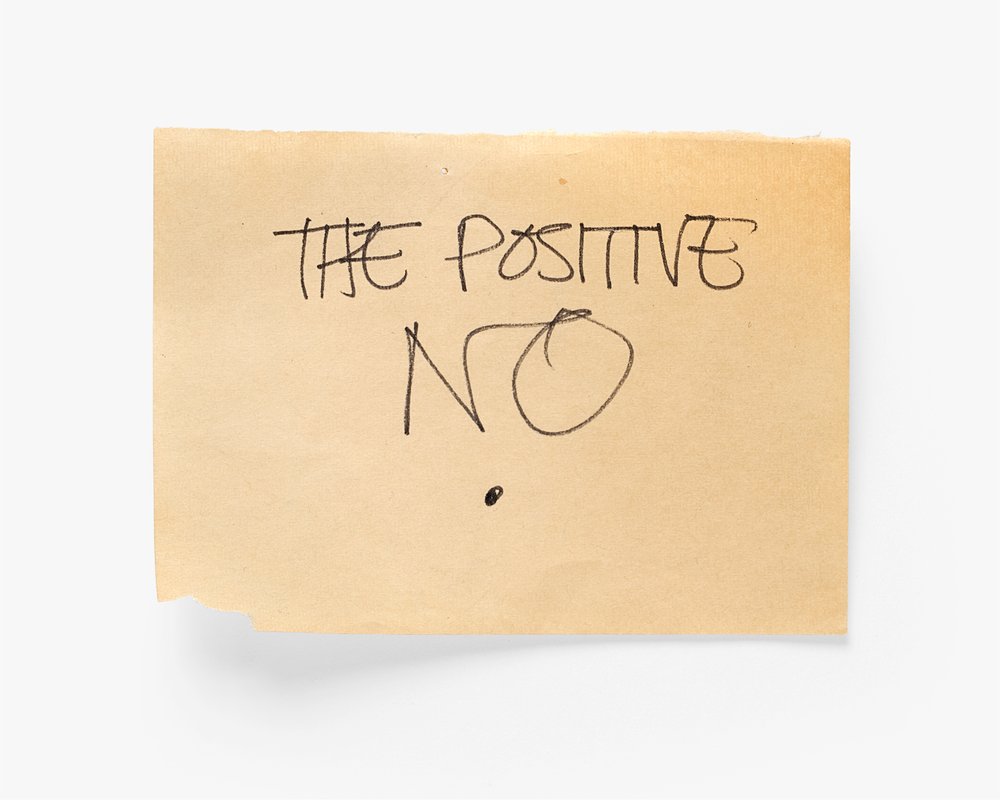

This exhibition highlights Ray’s hand talents and graphic skills, including packaging, facility with pattern, color, and collage, ease of crossing media, ability to work on a small scale, as well as understanding of structure, space, and movement. Several items are ephemera, i.e., items that, when produced, “were not intended to have originally expected to last a long time or were specially produced for one occasion.” Ephemera is often marginalized by historians, none more than the humble list, including those jotted down quickly and/or featuring doodles. This show invites us to re-think the humble list, and admire what film director and close Eames friend Billy Wilder referred to as Ray’s ability to make art out of a two-line note. The exhibits show her seemingly unerring ability to mix colors and forms in ways that added movement and depth to two- and three-dimensional objects, and her facility with scissors and the “Cutting Papers” associated with Froebel-style early years learning through play that were popular when she was young. Her affection for such papers and use of craft skills associated with progressive early years learning were regarded as outmoded and irrelevant to adult modern life by many but neither Ray nor Charles had any such hang-ups.

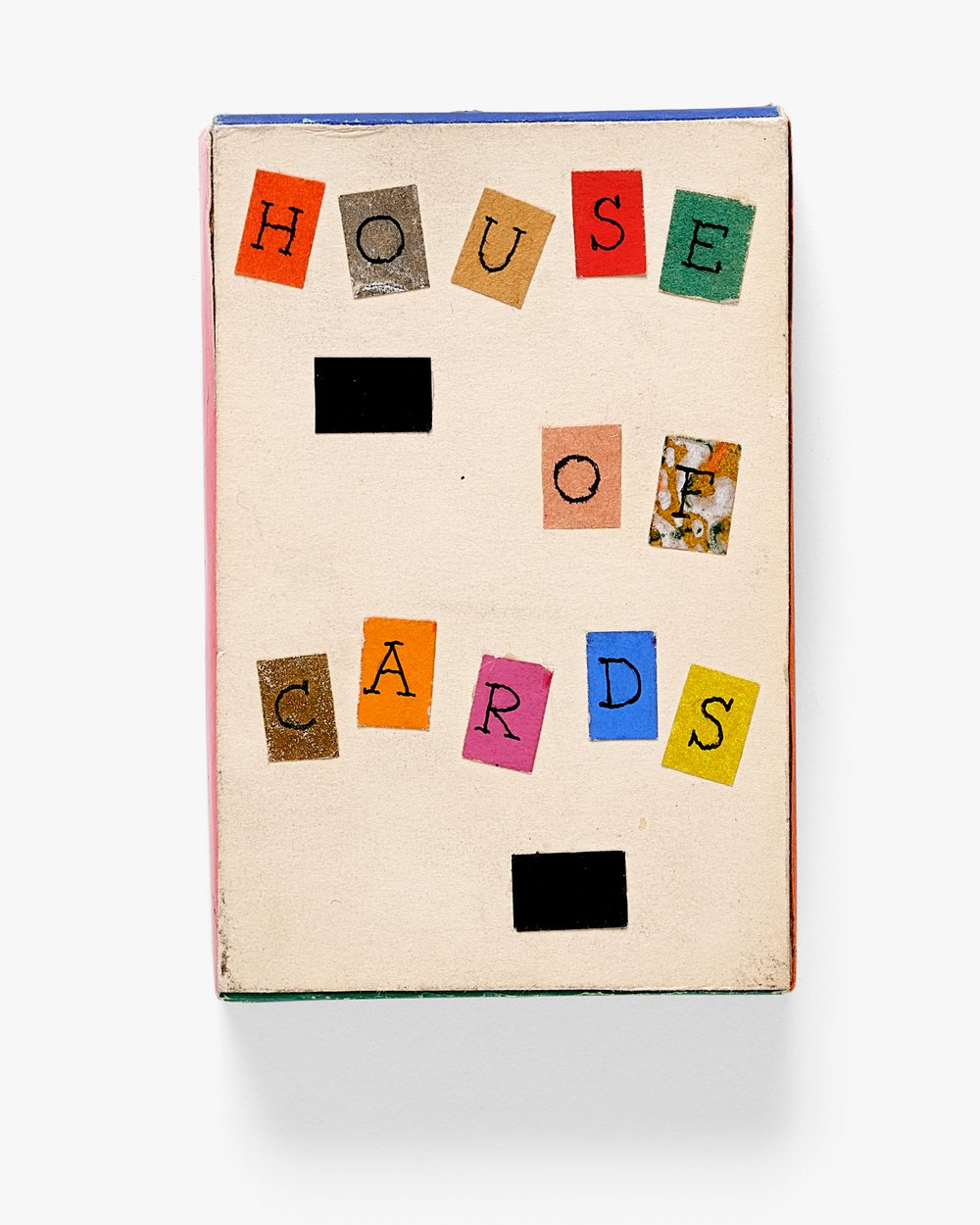

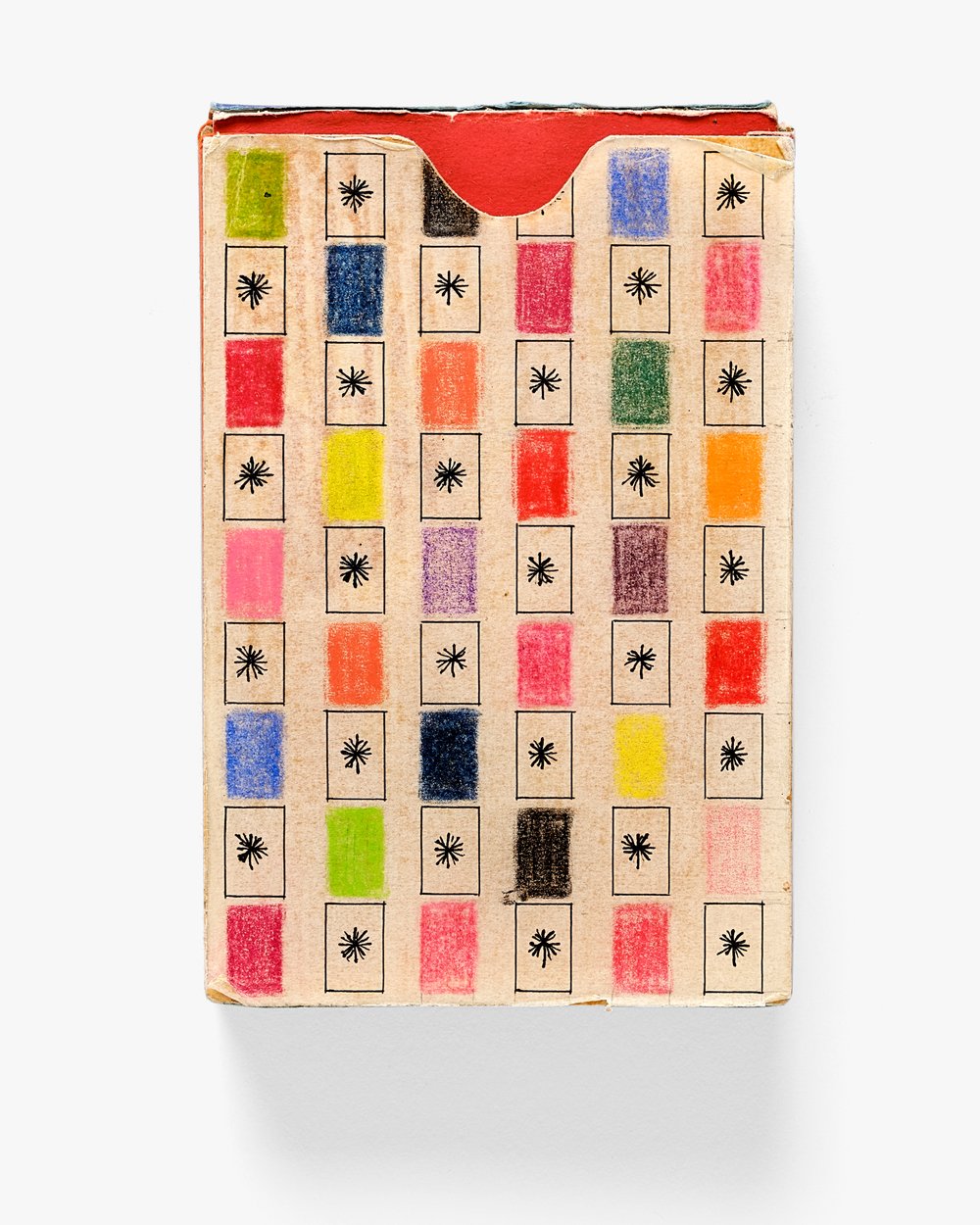

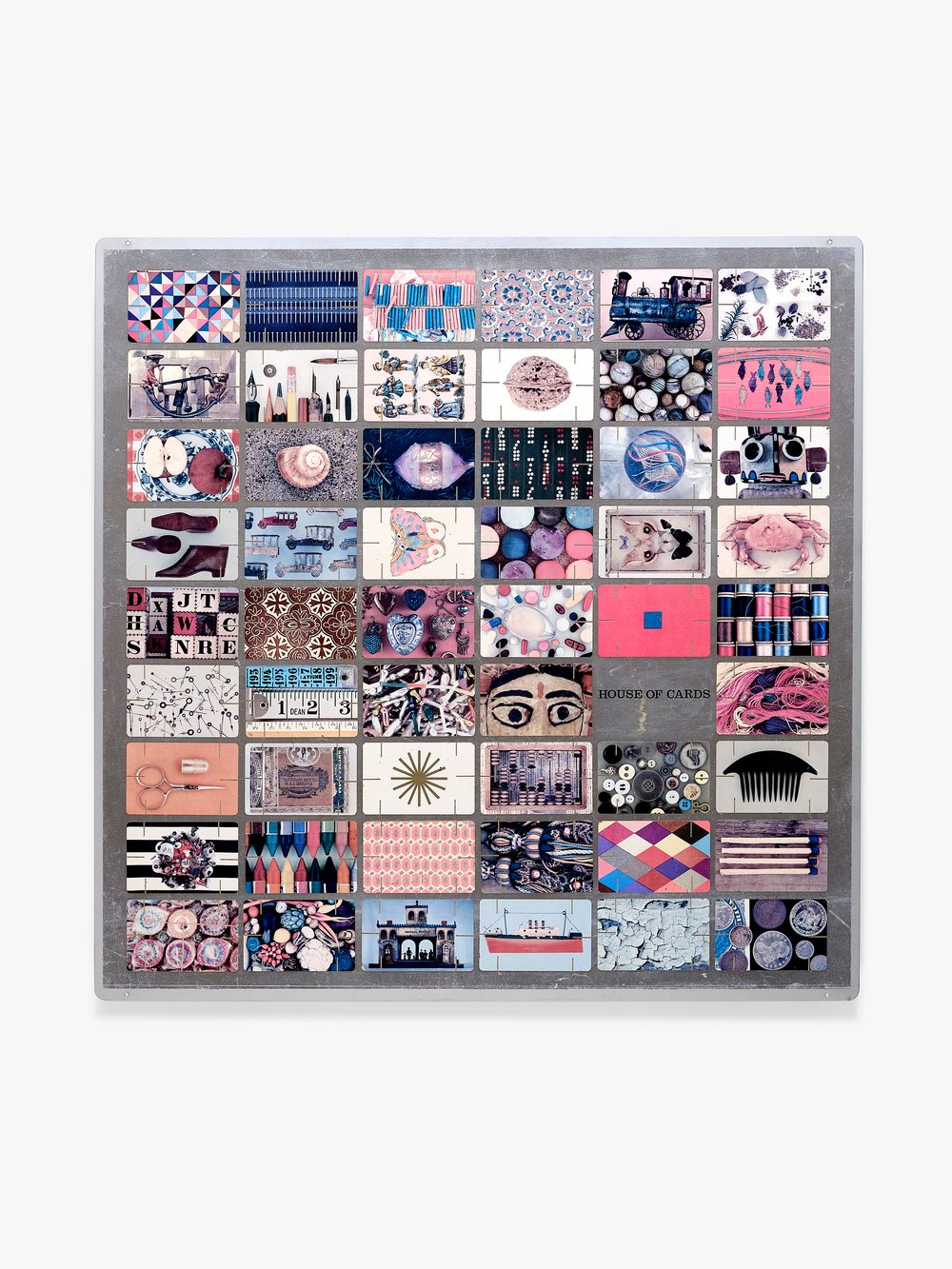

Designing toys was a logical outcome of them taking their pleasures seriously, and vice versa, and their determination not to separate fun and play from life and work. Ray noted the similarity of the thinking behind the Eames House (1945–49) and The Toy (1951), namely to make “a structure … a large form with large volume, with a series of materials” that could be then contained in a small box. House of Cards, she explained, came from thinking about new ways of playing with cards by using “a known base,” i.e., the conventional house of cards built by balancing cards one upon another. Each Eames card had slots that enabled the cards to be slotted into one another.

Ray’s handmade maquettes for the House of Cards pattern deck are featured alongside original artifacts that were photographed for the picture deck.

One way of grasping the extent of Ray’s talents is to consider the formation of this modest but super-talented, independent, and open-minded woman with twinkling eyes and an equally twinkling mind, strong sense of humor, and deeply holistic approach to life and work who spent much of the 1930s in and around avant-garde art circles in New York City before meeting Charles in 1940. At 27 years of age, she was seeking a new direction after nursing her mother through her final illness, and en route to building a house in her native California. He was 33 and must have been bowled over by her and her passion for, and knowledge of, so many things he was also passionate about, especially art, film, design, and structure. Ray later explained that what underpinned her approach to everything, from art and dance to literature, was fascination with structure, something that came to Charles through architecture.

She attributed her holistic approach to life and work to her parents who were “always interested in everything” and considered there was something akin to Zen philosophy about her upbringing. She spoke of the strong sense of quality, discipline, and hard work her parents gave her, along with getting enjoyment out of work and daily life, and a determination to accomplish what one set out to do—qualities she recognized in certain other important people in her life, including her childhood ballet teacher, modern dance pioneer Martha Graham, Hofmann, and Charles. Her love of performance dates back to her childhood; when she was born her father (a former mesmerist) ran a top-end vaudeville theater in Sacramento, California.

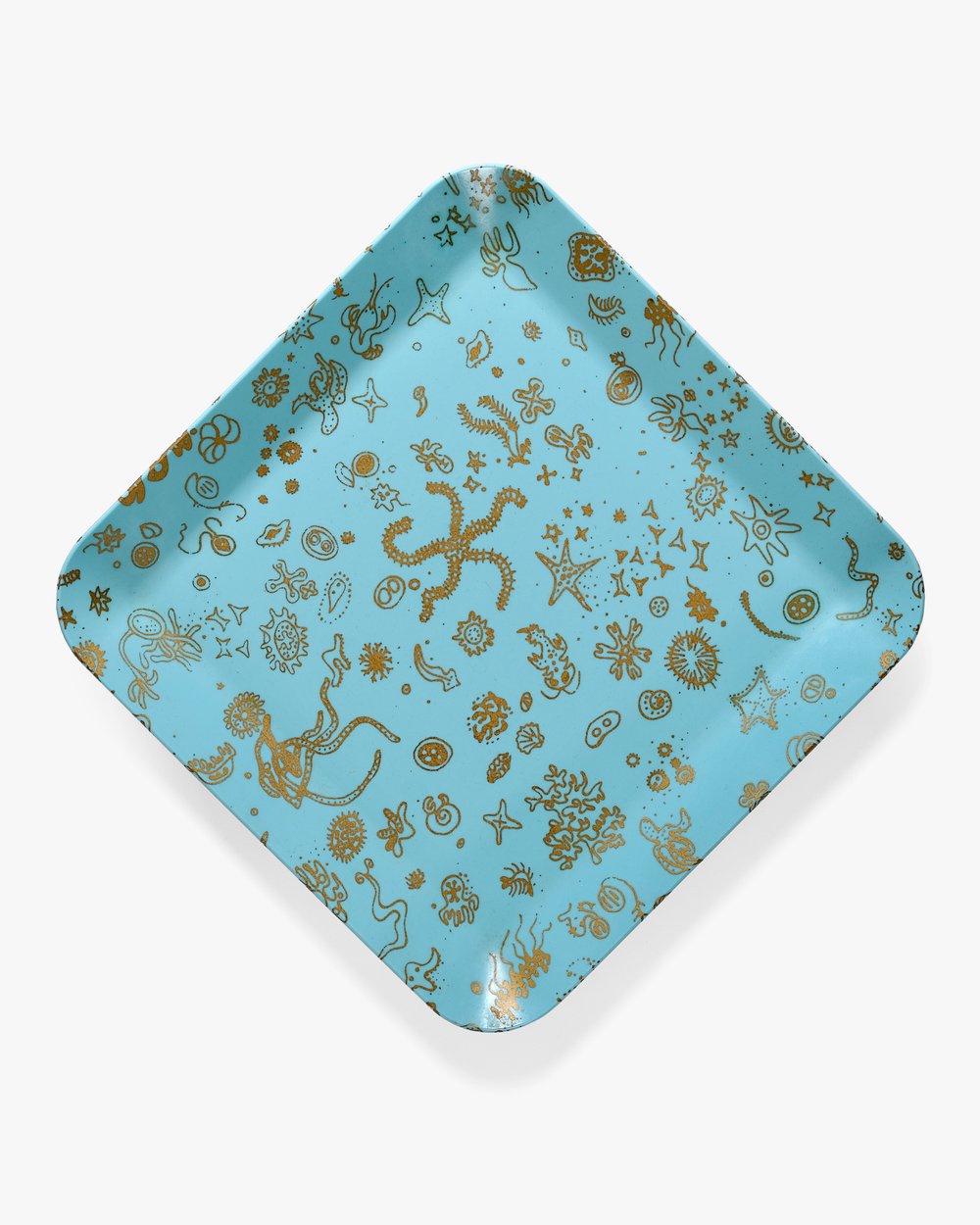

She showed an early aptitude for art, and focused on art, literary studies, and French in high school where she chaired the decorating committee for the annual football dance before graduating in early 1931. During a semester at Sacramento Junior College, she took more vocation-oriented courses in fashion illustration and commercial advertising (a term then used for graphic design). The former reflects her interest in fashion and facility with sketching and color; the latter her interest in graphics a decade before her contributions to Arts & Architecture magazine and textile designs such as “Sea Things”, “Crosspatch”, and “Dot Patterns” that brought together her interest in structure and facility with pattern. From fall 1931 to summer 1933, Ray received an excellent holistic arts education at junior college level with a special focus on art, modern dance, music, drama, and literature at the prestigious May Friend Bennett School near Millbrook, New York, which sought to produce independent, broad-minded, and well-educated young women. Ray spoke of the stellar faculty and the stream of impressive visiting practitioners from New York City (only 85 miles away).

A family of prospective stools rendered in plasticine were among the items on Ray’s worktable in May 1960. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Walnut Stool, 413 was originally designed for the Time & Life Building at Rockefeller Center in New York.

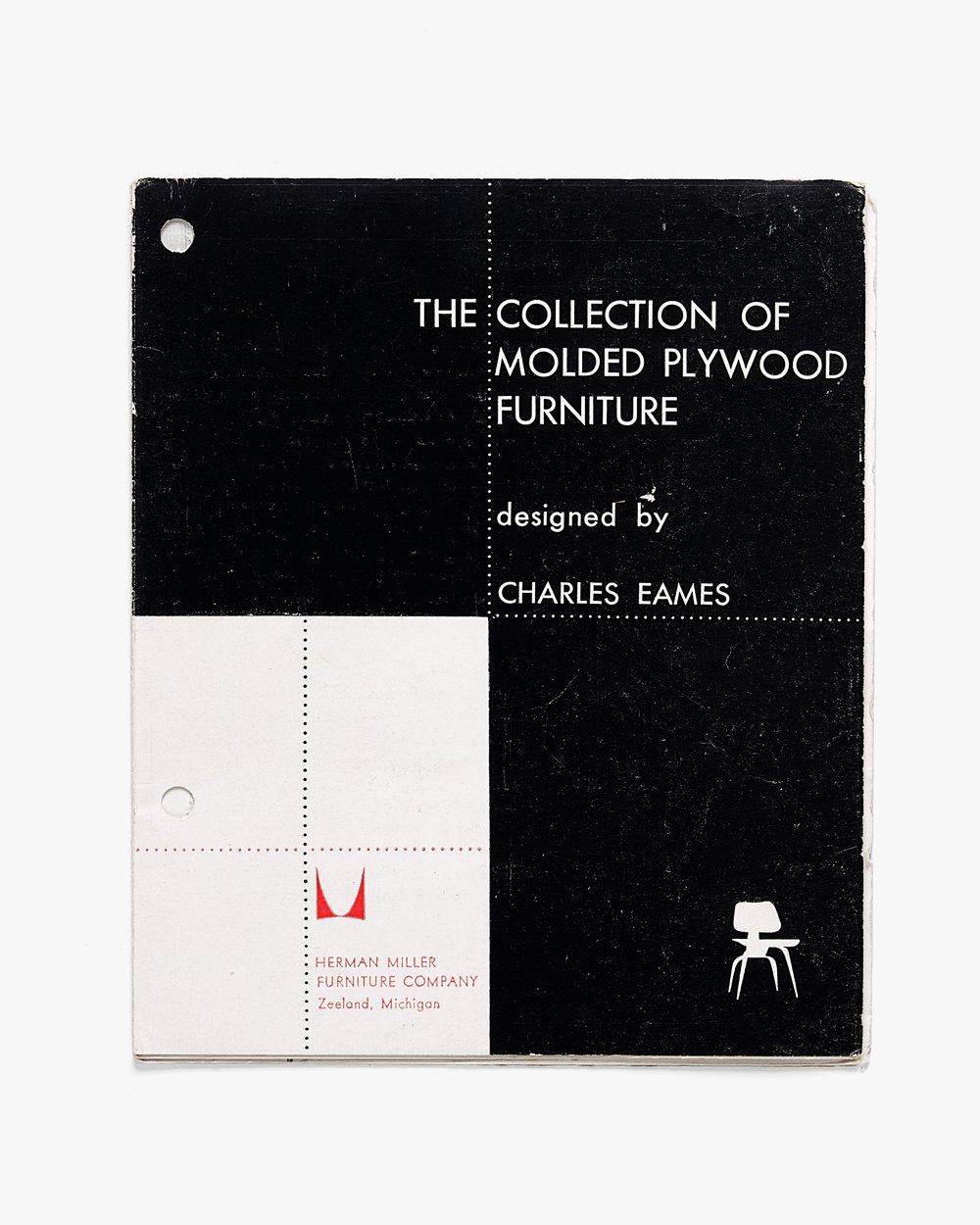

After Bennett, Ray considered studying engineering but moved to New York and joined the studio of Hofmann, whom art critic and champion of Abstract Expressionism Clement Greenberg considered “the most important art teacher of our time.” Hofmann became a friend and mentor. Ray recalled going to the movies with him and them bumping into Mondrian on the street one day while out in the city. Among the first generation of American artists to espouse abstraction, Ray was a founder-member of the American Abstract Artists (AAA, 1936) which promoted non-representational art and looked mainly to European artists such as Picasso, Bauhaus abstractionists, and Mondrian. The influence of the latter’s geometric forms and bold palette is evident in the facade of the Eames House (1945–49) and Eames Storage Units (1949–50), while Ray’s interest in the more organic forms of Arp, Miro, Picasso, and Kandinsky are seen in her 1940s graphics and the forms of Eames molded furniture. Hofmann’s bold, joyful use of color and emphasis on structure chimed with Ray’s interests, and his “push and pull” technique that created movement and tension within flat canvases thus creating a sense of three-dimensionality is evident in the tensions between the two main pieces of the Eameses’ molded plywood chairs (1946). While in New York City, Ray attended classes in modern dance with Martha Graham and leaders in the modern dance movement in order to better understand structure in relation to the movement of the body in space, which was somewhat akin to the movement Hofmann aimed at in his paintings.

That Ray saw everything as interlinked explains why she was puzzled when asked if she regretted giving up painting (a medium she was feeling dissatisfied with by the late 1930s) to work with Charles on what turned out to be design, film, and multimedia projects. She considered she was simply changing her palette. One can also think of it as her exploring yet another interrelated medium and means of communication. Indeed, she went to Cranbrook to expand her craft and design skills by taking Harry Bertoia’s metalwork class, Marianne Strengell’s weaving class, and Charles’s design class. Furthermore, she was one of a small group of students who helped Charles and architect and sculptor Eero Saarinen with their entry for MoMA’s 1940 Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition that included industrially mass-produced plywood chairs with complex curves. Ray worked on presentation drawings and therefore was familiar with the project. Thus, when the plans she and Charles had for making films about art and architecture came to naught, and Eero opted out of the plywood project when the chairs proved impossible to mass-produce, she was already vested in the project. Charles, who had worked in partnerships ever since working independently, and briefly with Eero Saarinen at Cranbrook, formed the last partnership of his life with Ray, and thereafter they both changed “ palettes” according to the projects in hand. ❤

—Essay by Pat Kirkham

—Photography by Nicholas Calcott

At work in the graphics room in May 1960, Ray was integral to every project the Eames Office undertook. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Explore All Artifacts

Dive into the exhibition—item by item. Clicking on an entry takes you to an artifact detail page containing pertinent details, more images, and in the case of some objects, curatorial notes.