Design Q&A: Formafantasma

In museum exhibitions and corporate projects alike, Formafantasma is pushing design to consider ecological impacts and the imperative of social justice.

From their Milan studio, Formafantasma’s Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin discuss their vision of design.

On the surface, the parts that make up Formafantasma’s studio practice appear dichotomous. Its two principals, Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, are partners in both life and work; their office is divided into one arm dedicated to speculative research and another to tangible design commissions; and the name of their studio is an oxymoronic Italian compound word meaning “ghost form.” But Trimarchi and Farresin don’t see divisions in their work—symbiosis inspires Formafantasma to produce products, thinking, and exhibitions of enduring value that consider and serve an ecologically dynamic range of end users.

Trimarchi and Farresin met in Florence while completing their undergraduate studies. Shared interests motivated them to collaborate on a joint thesis project and then apply to their graduate studies with a conjoined portfolio to the Design Academy Eindhoven. In 2009, they founded Formafantasma, which now operates offices in Rotterdam and Milan. Since their debut, they’ve designed furnishings for the likes of Hem, Flos, Fendi, and Roll & Hill, in addition to producing talks and creating exhibitions for venerable institutions worldwide.

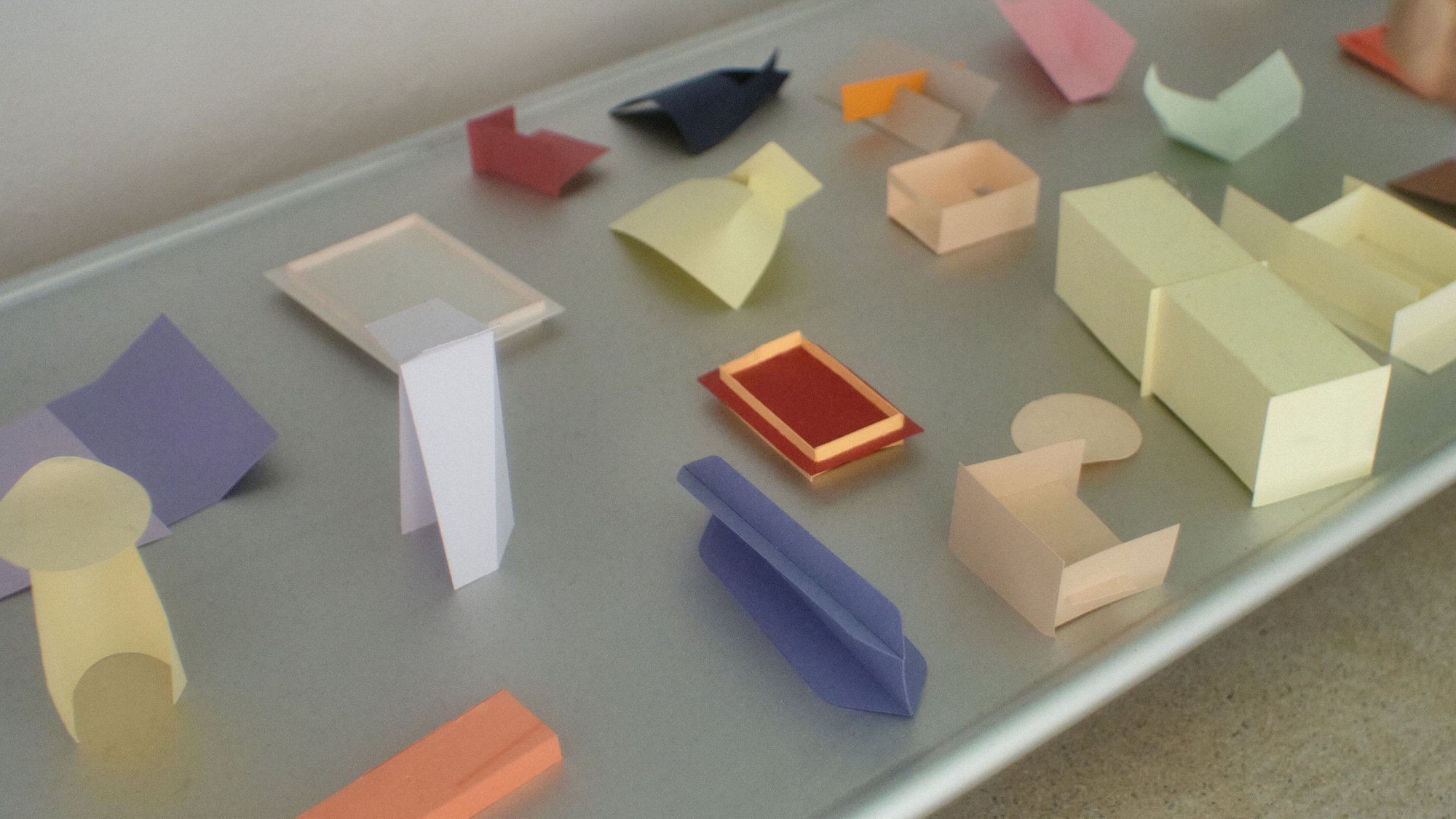

The studio’s research delves into material experimentation and hypothesizes new systems of production, placing a strong emphasis on ecological sustainability. For Botanica (2011), the studio posited the question: What if petroleum-based plastics had never been invented? To explore this, Trimarchi and Farresin researched 18th- and 19th-century–era polymers derived from plants and other organic sources. Formafantasma then recreated these materials and molded them into bowls and amphorae to demonstrate a more sustainable use case for plastic that isn’t derived from petroleum. The resulting collection was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and celebrates the possibilities and limitations of these materials in designs both intricately detailed and rough-hewn.

Tension between decorative and unfinished elements in the Botanica collection convey a sense of material honesty while also recognizing the need for these objects to be attractive to consumers. In these beautiful vessels, Formafantasma slyly confronts the conflict between using less extractive, less slick, yet more sustainable means of goods production while also admitting that the global West lives in a somewhat superficial era of conspicuous consumption. Navigating this contradiction is fraught, but Formafantasma finds that there is opportunity in opposition. Through this and other work, the studio conducts research to then smuggle the resulting ideas into more commercial projects, and conversely, they learn from their commercial clients the intricacies of design production at an industrial scale. The insights then spur topics of independent research.

The interplay of these interests is seen in a 2023 exhibition commissioned by the National Museum of Oslo called Oltre Terra, which critically investigated the production of wool. Formafantasma researched the rich history of cultivating Merino wool and designed a museum exhibition to communicate its story, beginning with the breed of sheep raised over generations to produce wool and the cottage industries that formed around it. Their body of research concurrently informed Tacchini Flock (2023), a study developed for the Italian furniture brand Tacchini that ultimately advised the company to swap its upholstery lines’ filling from unsustainable synthetic foam to sustainable wool. And recently for Artek, Formafantasma developed an iteration of its ongoing Cambio project, which analyzes the timber industry’s impact and first debuted at London’s Serpentine Galleries in 2020. The 2022 study and exhibition for Artek, held at Helsinki’s Design Museum, compared the rate of the Finnish furniture company’s local timber harvesting with its production of hard goods. The resulting report delivered 30 strategies for how the company, by 2050, could reach a sustainable balance with the natural resources from which it extracts.

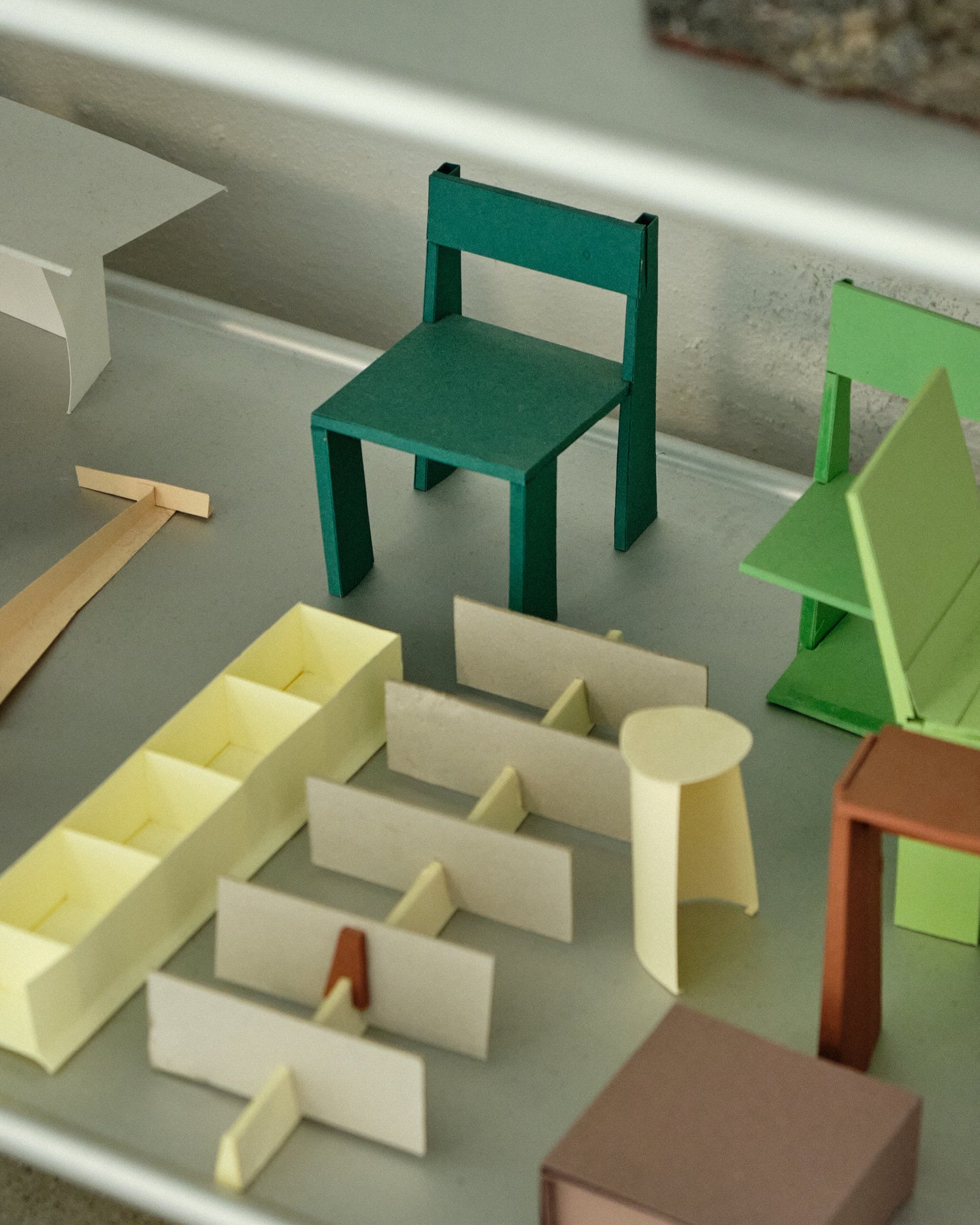

It’s not often that clients take risks at the systemic scale that Formafantasma enjoys operating, but even in largely commercial projects, their deep thinking is still felt. With the T Shelving (2022) for Hem, the studio designed a slick storage system that can be shaped and expanded over time, enabling evolving use cases and minimizing the risk of “throwaway” furniture. T Shelving is made almost entirely from extruded post-consumer recycled aluminum. The use of recycled materials results in less energy expended for material sourcing and transport, which drastically pares down the amount of carbon emitted throughout the production process as compared to one using virgin aluminum.

Formafantasma strives toward an ecological balance reminiscent of what Charles Eames advocated in his 1951 speech at the Aspen Institute, “Design, Designer, Industry.” Eames presaged how profit-driven postwar goods production for the American middle class may trample values that celebrated sustained ownership of designed goods like sofas, appliances, and housewares in the quest to sell more trend-driven disposable stuff, not better stuff. “There must be goodness all the way down the line,” he said, and called for an “integrated design program” to deeply consider the design and production of goods at scale. A truly ethical design practice, in the eyes of Formafantasma, is not anthropocentric. It recognizes that a designed product encompasses many different relationships and beneficiaries—not just the end consumer. And a truly good design considers the labor that goes into producing the product while also accounting for all contributors, such as the natural environment, that enable its existence. In this way, the generosity implied in creating a new design to better the lives of us humans and other living beings, must be embedded in the system that wills it to be.

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame Amic presents Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam!, we posed those same questions to Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin of Formafantasma.

Q: What is your definition of design?

A: It’s very difficult to give a definition of design. First, we think it is important to recognize that design can be a force for positive social, cultural, and ecological change. But it is also by nature a tool that is at the service of a client request, and it is often a tool for the design of objects that should be desirable—for instance, if we are talking specifically about product design. In that sense, design is also a tool in the hand of marketing as well as capital expansion and accumulation. It’s important to acknowledge that design can offer solutions for real-life problems—both for humans and even for non-human species—but it can also be part of the problem. We don’t believe that design is only a force for positive change; it can also be dreadful.

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: No. There are definitely artistic components in design, and design belongs to visual culture, so of course, designers and artists share similar tools. But design is not necessarily an expression of artistic practice, even though we present our work in the context of museums. There are differences in the disciplines, and also, economically, it’s a different market, it’s a different way of approaching work—it’s a different way of working. We work very well with artists. We definitely share similar thinking, but very often our preoccupations are different.

Q: What are the boundaries of design?

A: It is very difficult to define what the boundaries of design are, even if there are disciplinary boundaries. In our studio, we are interested in whatever we can do to challenge those boundaries. But that’s also why we’re not interested in talking about our practice as an artistic practice. Because we prefer that the questions that we raise with our work—or the answers we offer with our work—should be contextualized in the design discipline. This does not mean we are not interested in expanding and pushing the boundaries of what design is.

To give some context: One definition of design is that it is a natural human striving for making changes in the environment where we live as humans, to make it more comfortable. Thus, design is an “attitude” that is innate in humans. But design is also a discipline that has been developed in conjunction with the industrial revolution. So we can’t define what the boundaries of design are, but the boundaries of the discipline of design have definitely been defined in conjunction with the industrial revolution. As a practice, we are interested in expanding those boundaries, but not positioning our practice outside of the discipline.

There is not one ‘user’ but an enormous quantity of users who are not only the individuals who buy and own the object, but who are all the other people that contribute to its creation.

Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin

Founders

Formafantasma

Q: Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: Because of the way the two of us have been educated in the Italian and Dutch contexts, our understanding of design is very much a Western understanding of it. For a very long time, design has focused on one environment, or one reality—which is a specifically Western reality—and it’s struggled to understand, for instance, that whenever you design now, you design for the globe. This means that we should realize that, for instance, when an object is recycled, there are different realities where that object is encountered. There are different techniques, different humans, and different machines or humans interacting with the objects. And so you need to make sure your design encompasses all these realities.

While I appreciate the idea of a user-centered design, it is also extremely narrow as a perspective, because if we consider the user and the privileged environment that the designer thinks about, this mindset excludes the people who assemble objects, the machines that produce things, the materials that are extracted, the distribution of goods, and the raw materials that need to be transformed into the final product—to give just a few examples. So we believe that what we need the most at this moment is a mindset that goes beyond the user. Or to phrase it differently, we have to remember that there is not one “user” but an enormous quantity of users who are not only the individuals who buy and own the object, but who are all the other people that contribute to its creation.

Q: Is design a creation of an individual or a group?

A: Sometimes it is the creation of an individual, but whenever we as a practice engage in more complex subjects, we need the participation of many others’ contributions, skills, and knowledge. So we would say, no, it’s not an individualistic practice.

Q: Is there a design ethic?

A: Definitely. But we wouldn’t say there is one ethic of design. First of all, when you are a citizen, how could you not be confronted with ethics, especially when you are grappling with questions relating to work? When you are doing intellectual work that is not a form of labor, there is definitely a political component to it, and there are inevitably ethics that you need to adhere to. What are these ethics? It depends on the way you work and the questions you raise when working. While developing design, we reflect on many issues that are raised from ethical questions, or by trying to find an ethical position towards our practice. Working with design, we inevitably wonder about the why’s and the deeper reasons behind what we do. When we simply decide to accept work, or refuse a project, we are confronted with an ethical question.

Q: Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

A: Yes, but the concept of usefulness should be interpreted as much more expansive than we often think of it. Because the things that you don’t “use” are useful. Ornamenting a Christmas tree, decorating our body, or choosing one object over another are not necessarily useful to survive in a physical sense, but they are definitely “useful” in a broader perspective. I think the idea of what is useful and what is not has been oversimplified in design narratives, but it’s much more complex than that presentation. Similarly, the supposed assertion that “decoration is useless” is an oversimplification of the idea that modernism connected to how machines work, and the aesthetic that machines should have when producing things. But it does not mean that decoration is useless. We should consider what is useful and not useful from a much more expansive perspective than how it has been historically narrated in design books. Because if we took that to its logical conclusion, color would be useless.

Let’s forget about design for a moment. Simply making is an act of externalizing ideas. If we humans were not making things, I don’t think we would be the creatures we are. Thoughts are complex, and they are not bounded only by function. So we have to recognize that making has to do also with ownership, function, and comfort, but also with understanding and externalizing ideas.

Q: Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: We’re not Calvinist, so we don’t think pleasure is a problem. We struggle with creating rubrics for design. Is it only for pleasure? Of course not. Is it only for function? Of course not. We can’t oversimplify things to one dimension. At the end of the day, design is a response to life, and in that respect, it’s complex. It can be intellectual, rigorous, functional—but also, fortunately, it can also be frivolous and fun. We don’t think it should be a self-indulgence, especially if it becomes an industrial creation that is produced in mass quantities. The frivolousness then becomes a problem.

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: Yes, but not only. Again, it depends on what the function is. If you have an expansive idea of function, then there is also an expansive possibility of form originating from it. It is good when content and container merge. And it is problematic when the content and its form do not match. But we wouldn’t say it’s about form follows function—we would say it’s about form follows content.

Q: Can the computer substitute for the designer?

A: I hope not. Certainly not a computer. If we say that artificial intelligence is an intelligent being, then I’m interested in seeing what that intelligence has to say. Should it be substituted for the designer? Maybe the two could coexist. What I would be the most curious to see is how independent we are willing to make the AI. If we are still the ones feeding the information to the intelligence, then the question of whether AI could substitute for the designer is a very complex question. Maybe it’s not about substitution, but about coexisting on the planet with AI—in creative dimensions as well.

Q: Does design imply industrial manufacture?

A: No.

Q: Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

A: Yes! It’s not only that, of course, but it could be.

Q: Is design an element of industrial policy?

A: Yes.

Q: Does the creation of design admit constraint, and if so, what constraints?

A: Of course, but we don’t know what constraints, because we don’t know which kind of design outcome we are considering.

Q: Does design obey laws?

A: Yes. Even just the laws of physics. And the laws of common sense, too.

Q: Ought design tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: Design can do both. It is more interesting to think about the permanent—which, of course, is never truly permanent. But what we like about the idea of something remaining permanent is that you need to think about the long-term. And thinking long-term means that you can’t think only about “an object” or “a solution,” but rather you need to think about larger systems. For us, it’s also extremely interesting to think about the ephemeral, which leads us to ask, How can you design impermanence without being damaging to the environment, and without contributing to a culture of disposability? We find both permanence and the ephemeral to spark extremely interesting questions.

Q: To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: We have a feeling that we should say it should address everyone, and it’s for everyone—but that is not necessarily true. And further, who is this “everyone”? It was probably much easier in the ’70s, because “everyone” meant only the different classes in European society. Now everyone really means everyone. It means every single person in the world, and I think this “everyone” is not only about humans. We don’t think that somebody can ever address “everyone.” Yet it is inevitable that whatever we do in design and production—mostly in production—is going to have an impact on everyone. So instead of a focus on “addressing,” we should have an awareness that whatever we do is going to affect everyone on the planet. Producing things means shifting the environment and the unstable surface we live upon. From time to time, we can address works for different audiences and different people. In light of the climate crisis, we have to shift our concern from who we are addressing to the fact that inevitably we are going to impact everyone. This entails a sense of responsibility more than dedication—a recognition that whatever we do as humans on the planet has a collective effect.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises while practicing the profession of “design”?

A: Not forced. We accept the compromises. Our practice is a constant compromise. Even if we structure it in such a way that, for instance, we do independent works, or work commissioned by museums, or other commissioned work, we think the nature of design is searching for compromises—and finding a common ground. Because if you’re trying to propose solutions to a problem, that solution will always be a compromise. I think idealism—total idealism—does not actually fit with the design practice.

Design is muddy. It’s a dirty, muddy, wonderful endeavor. I’m thinking of Donna Haraway’s book Staying with the Trouble—which is hinting at the idea that the world we live in is unstable and complex, so the best way to understand how to act is to accept the world’s muddiness—that it’s confused and problematic. Regardless, we need to remain in it. Design is that discipline. And the mud I’m talking about is the fact that design simultaneously encompasses economy, social changes, culture, politics, aesthetics, and you cannot pick it apart from all these things.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

A: A very good commissioner leads to very good outcomes, so a very good primary condition for its propagation—and its creation—is a very good question to start with.

Q: What is the future of design?

A: We have no idea what the future of design is. What we can hope for—and we’re specifically referring to our practice that originated within product design—is that design would develop in such a way that companies and clients will ask designers to operate on a systemic level, not only a product level—which is sometimes very often happening. But in the majority of cases, design is still seen as a form-giver, and form is limited to the form of the object, not to the form of the system that creates it. ❤

Jordan Hruska is a Brooklyn-based journalist and critic who writes about architecture and design for the New York Times, The Economist, Domus, and Architectural Digest, among other publications.

Jonas Fogh is a Danish photographer and cinematographer based in Copenhagen.

Klaus Langelund is a former art director from Denmark now working in both photography and film direction.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.