Shelf Life

Bill Stout’s legacy rests on his passion for books about architecture. In this condensed oral history, he shares his story.

In Japan, the government gives an honorary award called the National Living Treasure to those who have a unique and often unreproducible mastery of a craft or skill. These individuals are known as “Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Properties.”

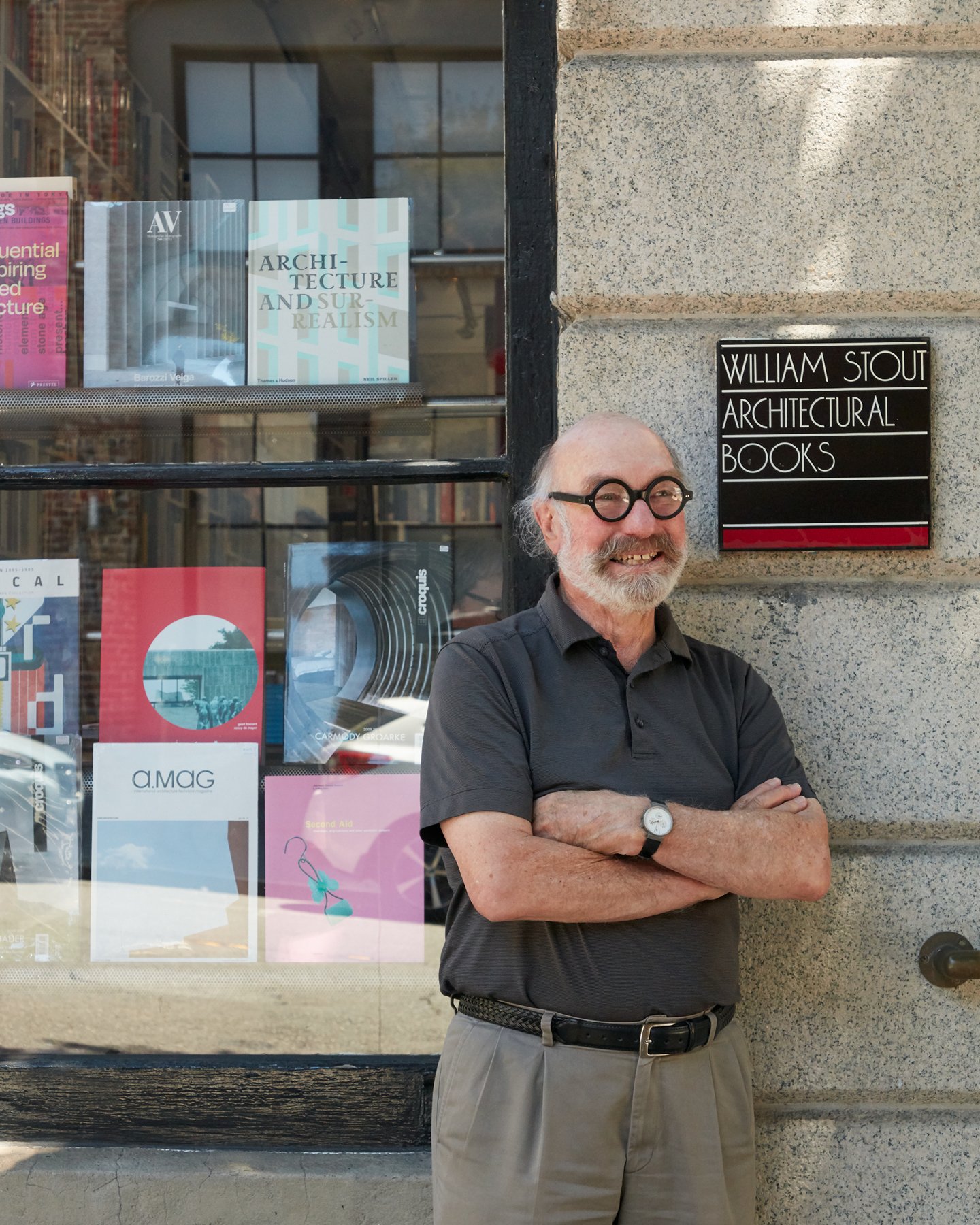

For almost 50 years, Bill Stout has fulfilled that role here in the US. As the steadfast and animating presence at William Stout Architectural Books, considered the most important design bookstore in the country, Stout has indelibly shaped the literature of architecture and design. He has published monographs on influential architects, collaborated on publishing projects with renowned figures including Zaha Hadid and Lebbeus Woods, and defined the visual references for legions of architects and architectural enthusiasts. When SOM wanted to build its in-house library, for instance, the firm turned to Stout—a curatorial effort he repeated for numerous other studios.

For most of its existence, the shop has been located at 804 Montgomery Street, in the shadow of the Transamerica Pyramid in downtown San Francisco. The so-called “804” has been the meeting place, clubhouse, and pilgrimage point for several generations of architects and designers the world over. The store’s bookshelves contain a vast treasury of architecture and design history, ranging from esoteric one-offs to the latest coffee-table monographs, and the shop has hosted countless luminaries. On one visit, I found Tadao Ando there, signing and drawing on any books that had his name on it (I stocked up).

I first met Stout in the mid-’90s, and started working with him in 1998 for a few years when he started his publishing house, William Stout Publishers. Over the years, I learned about his unique influences and stories: his childhood in the Badlands of South Dakota, where he attended schools at the airbases where his father was a pilot; the debut of his first shop, which he started through the encouragement of his then-roommate, Steven Holl; and of course his decades-long process of collecting rare books, gathered from some of the most important private collections in the country.

On the occasion of the Eames Institute’s acquisition of the bookstore and Stout’s personal collection, the Eames Institute’s Sam Grawe and I sat down with Stout to record an oral history of his career and legacy. Over two sunny days in Stout’s home office near Coit Tower, we spoke about his architectural education, his love for books, and the intangible skills he has preserved, and shared, as the premier design bookseller in the country.

This interview has been condensed and edited from the original conversation.

Dung Ngo: Bill, you’ve created a legacy in the field of architecture and architectural books. Do you recall when architecture first caught your imagination?

William Stout: In the seventh grade I saw a CBS special on Frank Lloyd Wright. I was taken by it. I think maybe the term “architect” sounded cool to me. So I began thinking about what it would be like to be an architect.

DN: Do you remember how you came across the documentary?

WS: I think it was a Mike Wallace interview on 60 Minutes. During the conversation, Wright built everything up about his career, almost as though he was saying, “I am king of the mountain.” I don’t think I had heard of Wright before that. He impressed me as a big star.

DN: So when it came time to attend college, you applied to study architecture?

WS: I did, and ended up in Moscow, Idaho, in 1960. The interesting thing about the University of Idaho architecture school is that it was really an art and architecture school. It had a small building with the art studios and the architecture department together. It was quite small, pretty intimate. The guy that ran the architecture program was Ted Prichard, from Harvard. He had a wonderful library in his office, and anybody could go in there and use it.

I got there, and I felt lost. I should have taken a year off. The first year was very heavy in the arts. You had to take two or three drawing courses in the art department. I did pretty well, but I wasn’t up to par with all the young people from Boise who could draw like hell. So during my junior year I decided that I would try to get out of school faster because I wasn’t doing too much. I took two summer school sessions and got out in four years instead of five.

One day I decided to sell books in our apartment. It didn’t have much room, but there was a big living room and kitchen. So we made that into a ‘bookstore.’

William Stout

Founder

William Stout Architectural Books

Sam Grawe: Where did you go from there?

WS: I went to Connecticut. In 1964, Paul Rudolph was at Yale and everything was happening there. I found a job at an office in Hartford—Stecker and Colavecchio. Strange place to be then, in that little firm of about five people. They gave me everything I wanted to do for three years, mostly schools and churches. That was when I started being serious about architecture. There were some really good people to learn from there. I took in all the lectures; I would go to Yale and attend Vincent Scully’s public lectures. Josef Albers was teaching there. Norman Ives was designing the art books. And Perspecta had just started, so Robert Stern was there. I’d go to Boston Architectural Center, and lectures at Harvard.

Rudolph was just finishing his works in New Haven and Hartford, like the parking garage. I used to collect the special-made bricks from Philip Johnson’s building on the Yale campus [the Kline Biology Tower]. That period was eye-opening for me, except I didn’t like New England. Growing up on the West Coast, I didn’t care for New England’s class system.

At one point, Paul Rudolph had quit and Charles Moore was coming into Yale. I wanted to go back to graduate school, so I created a portfolio, and worked hard to get an interview with Moore. When I went in to talk with him, he says, “This is not bad work.… You’re from Idaho and we have 22 positions and there are 422 applying. What do you think?” I didn’t say a word. I walked out and said, “Thank you very much.” I was an outsider looking in. In 1966 or ’67, I got in my car and came to California, where I got a job with Ernie Kump.

DN: What kind of work did you do with Kump?

WS: Kump had an office in Palo Alto and he had just finished Foothill College. He was the junior college architect at that time—we had eight junior college projects in an office of ten people. We were doing junior college works with Ben Thompson, with Perkins & Will. I designed the planetarium at Foothill. At that time, Foothill was the hottest thing going.

After a year and a half, I decided I’d try graduate school again. I met with Ernie, who I only got to see a few times a year, and he said, “Well, let me call up Dean Wheaton at Berkeley and we’ll see what we can do.” He gets on the phone right then. He says, “I’ve got a guy who’d like to go to graduate school, what do you think?” And Wheaton says, “Well, do a quick résumé and we’ll see what we can do.” I did a résumé over a weekend, and I ended up going to Berkeley. And that was ’68 or ’69, during the riots. Joseph Esherick was my advisor. I saw him once. As soon as the riots started, we didn’t even have to finish classes—we just got out of school.

DN: Who else was teaching at Berkeley at the time?

WS: Berkeley was really into systems then. That was the first year Christopher Alexander came and everybody wanted to get into his course. Everybody was carrying all the computer cards. If you got into his course, that was the big deal.

After Berkeley I got a job with Warren Callister. Warren sent me to Connecticut to work on a place called Heritage Village, which was the Victor Borge Estate in Southbury, Connecticut. At one time we were traveling back and forth. I had come back here to have a meeting with Warren, and we flew back to New York together. When we were there, we heard that Paul Rudolph’s Art & Architecture building at Yale had burned. We rented a car in New York and drove directly there, and it was still smoldering. I had never seen Warren so upset about something. And I never knew he would be into that building. He was very romantic, Warren Callister—a guy from Texas.

SG: How did you shift from architecture work to collecting books?

WS: I had gotten married in ’70 and then divorced in ’73. We liquidated almost everything. I put the remainders into a storage unit, and decided to go to Europe. But right before I left, I met Steve Holl at Sandy Babcock’s office. He came in to give a lecture on Louis Kahn—Steve had applied for a job at Kahn’s office, he had the job all set up, and then Kahn died. He gave a talk about that experience. Steve had just moved to San Francisco and was working at BAR [Backen Arrigoni Ross] while trying to start his own office. His parents had given him a house to do in Manchester—that was his first project.

When I went to Europe, I bought a lot of books and did a very good architecture tour. I went all over: London, Paris, Basel, Florence, and Rome. I was gone six weeks. Shipped a lot of books back—found a lot of nice bookstores.

DN: Did you have any kind of library before the trip?

WS: I had an art library, but I didn’t have a lot of architecture books—maybe I had technical things. I got back here and looked up Steve. We went out to dinner one night and he says, “Well, I’m going up to my parents’ house, why don’t you stay in my apartment while I’m gone? The lease is up in two months. I’m going to have to move.” I stayed there for two months, and when Steve got back, we found an apartment together.

SG: This trip you took to Europe, was that your first exposure to design books? What was it that attracted you to books?

WS: I used to go to New York to Wittenborn Books. You’d be there and in would walk Vito Acconci or Richard Meier. The old guy had this tie on and Jaap Rietman [another legendary art bookseller] was his assistant. It was an amazing place. It was small, but this guy knew everything.

DN: At some point these design books became important to you—how and where did that happen?

WS: Well, I wasn’t a very good student, but I always carried books, assuming people would think I was cool. I always had a book in my hand. I think I always knew their importance. When I started high school, in Mountain Home, they had a wonderful library. We got the New York Times every other week, late by a week, and I read the New York Times Sunday newspaper every week. I knew everything that was happening—I was really into art.

So one day I decided to open a bookstore and sell books in our apartment. We had a beautiful apartment. It looked out all over and it was high on the hill. It didn’t have a lot of room, but there was a big living room and kitchen. So we made that into a “bookstore,” which was just a round table with books all over. Most of them were from my own library, like the Le Corbusier set from Birkhauser or whatever. I had been communicating with Yukio Futagawa of Global Architecture, and I’d been buying a few books from him. He’d cut a deal with me and would send me books and I could pay him whenever. It was a nice way to work.

In that early period, I saw that you could basically survive on the local market. There must have been a hundred architects within 20, 30 blocks: Kaplan & McLaughlin, HOK, Skidmore…. And then all the small offices, like Marquis and Stoller, were right around there, too.

Catalogs published by William Stout Architectural Books. “Off Centre” was the original name of the shop. Photograph: Aaron Wojack

SG: How did you start to promote the store?

WS: I realized we’d have to do a catalog. And I stupidly didn’t want to use my own name, so I called the store Off Centre. The first catalog was just a sheet that you could fold out.

For the second one, I realized I had to buy a special envelope for it. I designed it myself, and it had quite a few books. One on Alvar Aalto featured a little cover of him and had a nice selection overall—probably a couple hundred books you could order.

SG: How long did you operate out of the apartment?

WS: Two or three years. I used to try to print the catalog at least twice a year. Number six was really big. I sometimes ask myself, “What was I thinking of?”

SG: By catalog three, you have moved to Osgood Place. By number four, you’re calling the bookstore William Stout Architectural Books?

WS: Yeah. On Osgood, the first room was the bookstore, and then there was a workroom and bathroom, with a bedroom behind them. And there was this beautiful garden in the back, where I used to have events and people like Peter Eisenman would come through. After a year or two at Osgood, I took on a consignment of architectural books from a bookseller on Sutter Street. I put those books into the bedroom, and I moved upstairs and took over an apartment.

I was practicing architecture at the time—next door to the store we had an office that Peter Van Dine, Jim Jennings, and I started. Susie Coliver started Arch there, and her boyfriend at the time, Dan Friedlander, started the furniture store Limn. So we had a modern furniture retailer, a bookstore, and an art supply store, all on Osgood. And then Mark Mack and Andrew Batey rented a little space there and they started Archetype, with Kurt Forster and Diane Ghirado. They wanted me to be involved in Archetype. Well, I don’t write very well, so I said, “I don’t want to be involved, but I’ll help you distribute it.”

A collection of catalogs published by William Stout Architectural Books over the years. Photograph: Aaron Wojack

DN: How was the bookstore evolving during that period?

WS: Charles Bassett, the head of Skidmore at the time, really liked the bookstore—he was into books. He visited one day and said, “Bill, I’ve got a really good library at the office. If you bring over 20 books every two or three months, I’ll get a library committee, and they can pick any of those books.” So I’d sell 15 or 20 of those books every time.

Susie Coliver ran the lectures at Berkeley, so we then got Berkeley to take the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies lecture tour. All those lectures came out here. Andrew McNair [the IAUS manager at the time] would introduce each one. Then we’d have a Christmas lecture every year where Peter Eisenman gave a talk at the Art Institute.

SG: You were on Osgood for several years—how did you discover the current space?

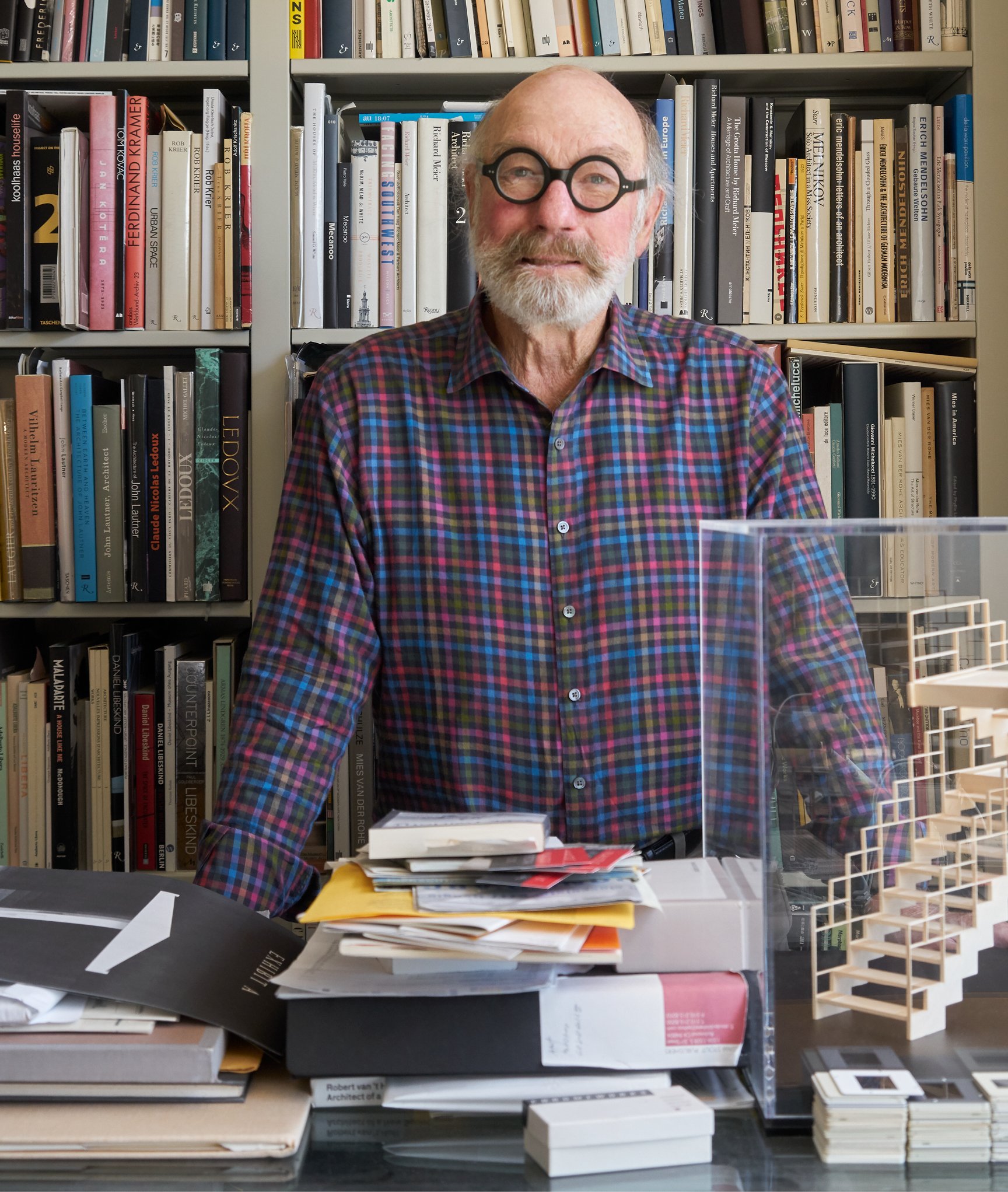

WS: Jim Jennings and I walked by 804 Montgomery, and it was available. It was 1,300 feet upstairs and 1,300 feet downstairs. We looked around and we really liked it, but it was almost three times the rent. The only way I could make it work was to move my office over there and put in a little apartment. I got a five-year lease for the space.

Downstairs, I put in a kitchen in the back. I had a half-circular library room where all my books were. And then there was a linear element that went through, which had five desks. And that’s where we did the SFMOMA museum show on modernism in architecture where I and three other architects were featured. The conference room was underneath, in the vault.

DN: So you lived there as well?

WS: I did, and then [my wife] Paulette [Taggart] moved to the Bay Area in ’85, so then I moved in with her, and eventually we started putting books down there, I’d say in the ’90s. I had that office until ’91, ’92. And then I closed my office and we made the whole space a bookstore. We put graphic design, landscape architecture, and history and theory down there.

DN: At that point, in the late 1980s, you became one of the premier bookstores in the country. And you had a lot of inventory.

WS: We had a good selection of books. We were doing almost $1.9 million in revenue yearly. Two hundred university and institutional libraries were buying from us. We would send a catalog, and it would come back marked up. Sometimes they’d want two or three copies of a book.

DN: I want to ask you about the design of the store. What did you have to do to get the store to look the way it does now?

WS: A lot of the bookcases came from Osgood, and we put that wall of books in. I had a good “steel man” and he built a ladder, which is hinged because we needed the ladder to get up to the top.

DN: You designed the ladder?

WS: I did it with another designer in my office. The steel man designed the wheels and everything. They’re beautiful.

DN: It looks to me that the ladder and some of the other elements are an homage to Pierre Chareau.

WS: I wouldn’t say Chareau, I’d say it was more Russian. The woman working for me was more of a Constructivist—so more El Lissitzky or Malevich. And then we have the front counter, which is almost Russian, and it was done by one of Mark Mack’s assistants.

DN: When did you start buying personal libraries?

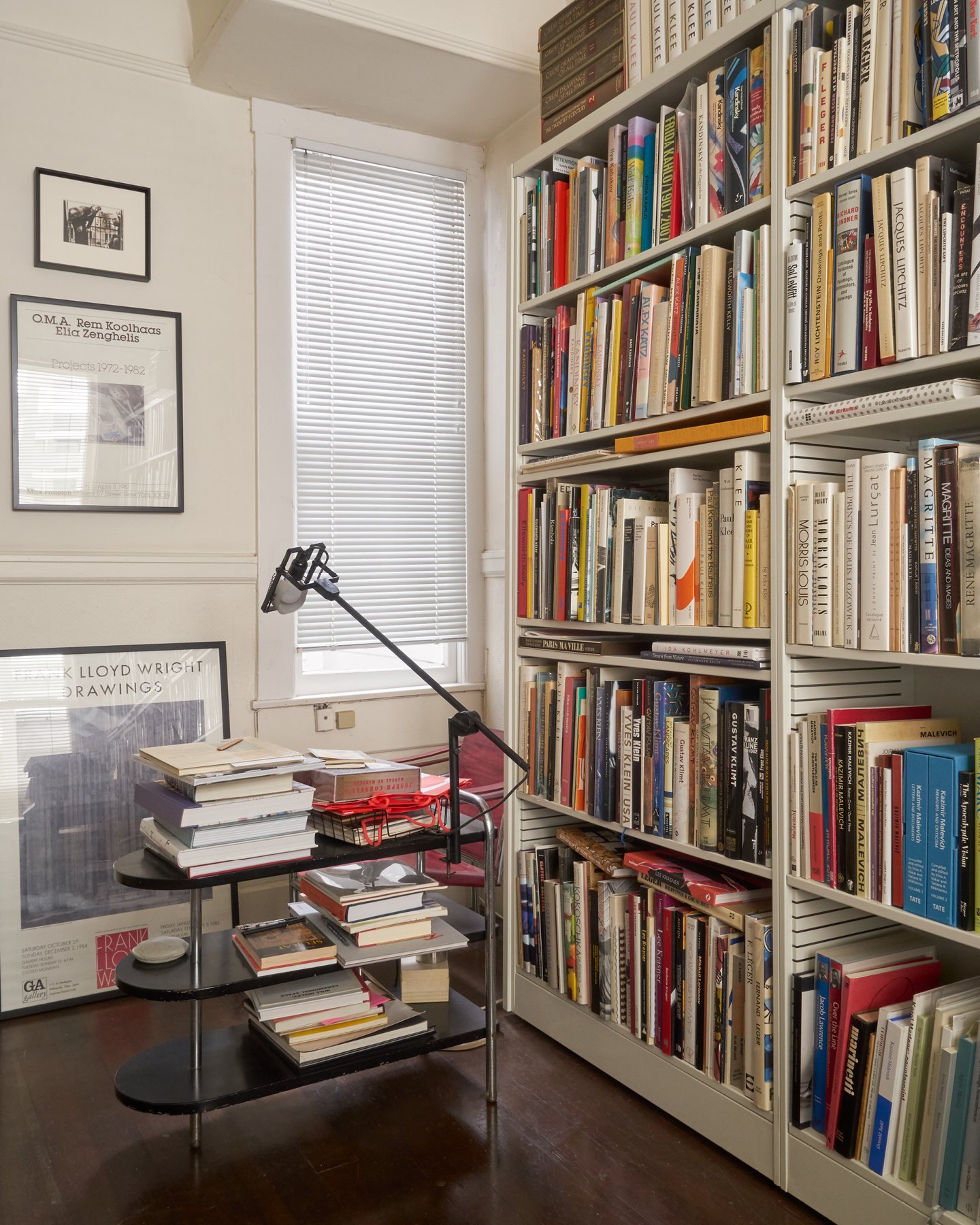

WS: When Kidder Smith died, Ken Frampton turned me onto his library, which was a great collection of books plus architectural documentation. When I was reviewing his library, I noticed a whole stack of photo books, and on my way out, his wife says, “Are you interested in the photo books?” I ended up buying all of them, and there was an original Man Ray in there. So usually what happens is there’s four or five of the books that will pay for the whole library.

SG: Would you cherry pick things for your own collection?

WS: Most of the good stuff would go into my own library. And in fact, that’s why you do it: you pick the best books for yourself, and then figure out how to sell the others.

It’s always fun when you get them back—many of the books we purchase originally came from us. I just bought a library from a client who had been buying from me for 40 years.

Most of the good stuff would go into my own library. And that’s why you do it: you pick the best books for yourself, and then figure out how to sell the others.

William Stout

Founder

William Stout Architectural Books

DN: As one of your projects, you published the Pamphlet Architecture series. You started Pamphlet with Steven Holl?

WS: Yes. When Steve and I lived together in the apartment that started the bookstore, we had a pretty good collection of publications from the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, and we were very enamored with what they did, with the graphics done by [Massimo] Vignelli.

Steve was trying to get work, so he left for New York. And when he got to New York the first person he looks up is Andrew McNair, who was running the Institute. Steve had designed a project called Bridge of Houses, a series of housing on the old High Line in New York. He did these beautiful drawings for it, and they were in a show at the Institute. At that point he comes up with this idea to do Pamphlet, and Bridge of Houses is the first one.

At that time, Steve had a studio on Avenue of the Americas at 48th Street, and in that building was a small printer, who printed the first. Steve came up with the idea for them, and then I would give him $500 and I’d get 40 copies.

SG: What was the overriding thesis of the series?

WS: The thesis was that at that time you only had Rizzoli, Wittenborn, and a few of the bigger publishers that wouldn’t publish Steve’s material. His thesis was they’re just cheap throwaways that an architect can do. In Zaha’s case, we went to the moon for her. Of course, she could not do anything that was just straight.

DN: How did you decide to start the publishing house?

WS: At one point I thought that there were probably a few architects on the West Coast with whom we could do books, and those projects would probably cross over and make some money. Some of them wouldn’t, but some of them would, so I decided to do it.

The Pamphlet Architecture series published by William Stout and Steven Holl included prospective projects by Holl, Zaha Hadid, Mark Mack, and others. Photograph: Aaron Wojack

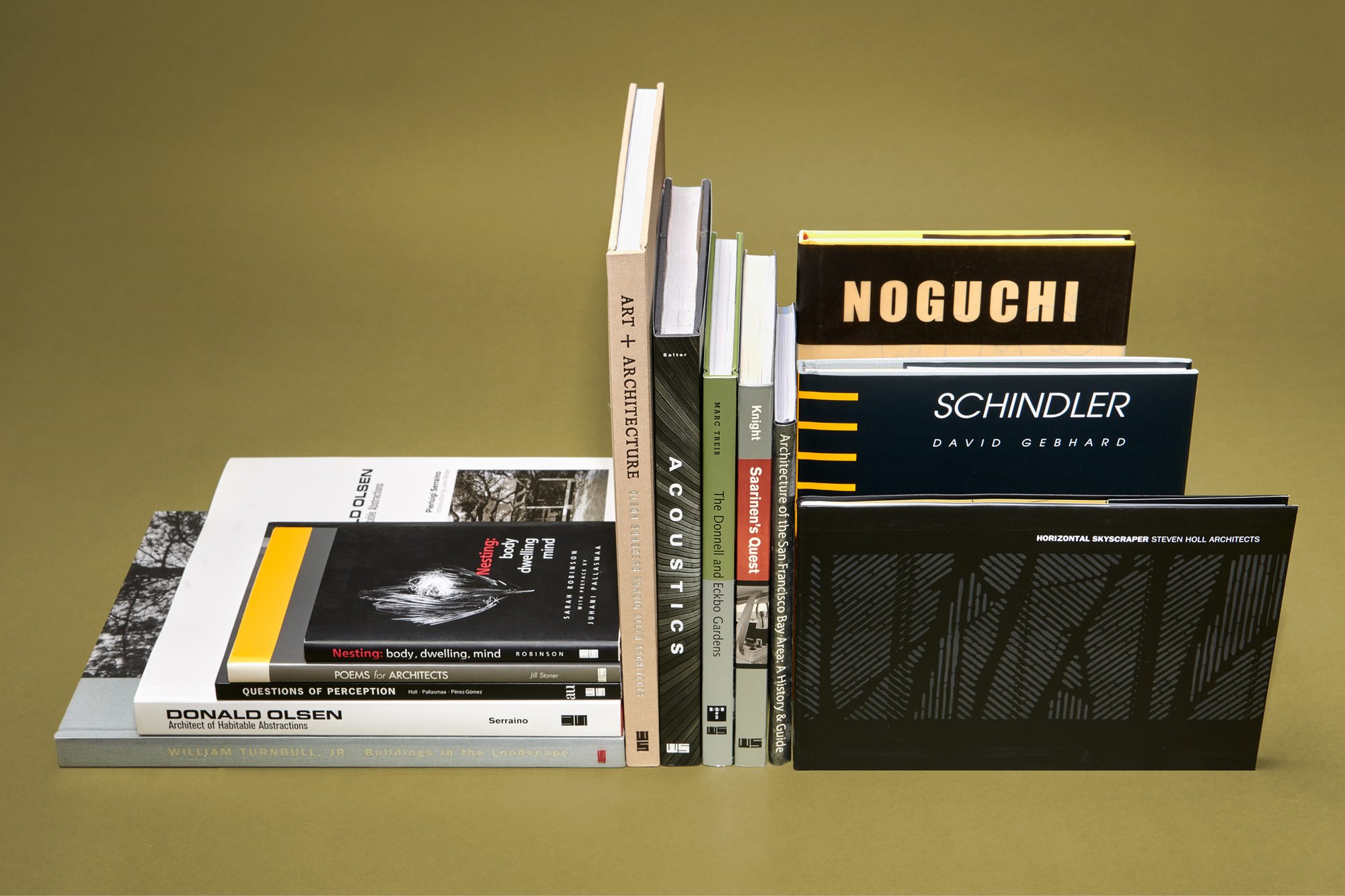

DN: Was Schindler, about Rudolf Schindler, the first William Stout Publishers book?

WS: Yes. When I decided to do a Schindler book, I looked at the one that David Gebhard had done, and it was a piece of garbage—it was written terribly. Schindler did color drawings, but it was a paperback edition and there were no color drawings. So I met with Gebhard and he invites me over to the archives and says, “If you want to, you can redo my book.” We wanted to change all the writing, and then we started getting into it and we started thinking, “If we change the writing, then we’re going to have a problem with him.” Then he died in the middle of the process, and so then we did the book.

DN: Then there were the books published with the Berkeley College of Environmental Design Archives.

WS: Yes, the Getty gave us funding for that, but we had to do six books. Mark Treib did the Noguchi book and UNESCO paid for half of that.

SG: Is there one book that you feel really stood out?

WS: I think that, architecturally, the Turnbull book is beautifully done. It’s printed well and the layout’s good. We had a tough time because Bill [Turnbull] actually would’ve put in some buildings which aren’t too good, but he passed away, and so we didn’t have that problem. And then we got the approval to do a new edition of Questions of Perception, and we did very well with that. I really liked the Schindler book. I think we did a nice job and the Schindler reads well. The Donald Olsen is nice, too.

Books published by William Stout Publishers include titles on Isamu Noguchi and Eero Saarinen, and monographs of Donald Olsen and William Turnbull. Photograph: Aaron Wojack

DN: Off the top of your head, what would you say is the most rare or important thing in your library?

WS: The rarest one is the German edition of the Wasmuth Portfolio, which is in two volumes.

DN: Where did that come from?

WS: A lot of people in Chicago ended up in Seattle, and there was one architect there who worked for Wright and had a complete set of almost everything Wright did. Before he died, he gave the collection to Professor Pundt, who was Steve Holl’s history teacher in Seattle. Professor Pundt called me maybe 25 years ago and said that he’d like to sell a collection, but he didn’t want to sell the Wasmuth if anybody would break it up. So I said fine, and I bought that, and there’s a lot of Wright ephemera in there.

I still remember unpacking that library. And I still do that Walter Benjamin thing—when you unpack a library, you start thinking about where you got the book, or how it’s set up.

DN: In light of that, how do you feel about your books being part of the Eames Institute?

WS: The idea of being able to share the material with other people is a lot better than having it sitting in my file folders. I’m excited to see the Eames Institute make it all work together through integrating the books and collection into their programming. ❤

Dung Ngo is the editor-in-chief of AUGUST Journal, a magazine about travel and design, and the publisher of AUGUST Editions, a bespoke publishing house devoted to visual culture.

Leslie Williamson is an artist, photographer, and essayist. She is the author of four books: Handcrafted Modern, Interior Portraits, Modern Originals, and Still Lives.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.